Victorian fairies were gauzily clad prepubescent girls, combining sexual allure and innocence. A surprisingly large number of people, including Sir Conan Doyle, believed they existed. Two girls famously produced a hoax photograph that many claimed for decades afterwards was proof that fairies existed. Fairies were fascinating. They also embodied Victorians' secret sexual fears.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

A society's cultural fascination tells us what they are afraid of, but cannot openly admit to. I grew up in the age of flying-saucer visits: crop circles and egg-headed visitors. Aliens were studying humanity to stop us heading for destruction; or because they liked anally probing humans. Almost one in four people, according to one survey, had seen a UFO or had an alien-related experience.

Here in the valley, we had the Araluen alien invasion of 1982. A respected member of the community's car was picked up by a flying saucer and thrown over a fence. Actually, the skid marks showed there might have been great speed and a sharp corner involved, as well as intoxicating substances. But the story stood. Because the aliens were also examining the valley every night.

The phone call would come about 2 am. "They're back!" I'd race outside and there they'd be, sweeping strange, shimmering, green and pink curtains of light across the valley, inexplicably starting and stopping again. What were they hunting for? Should we order anal-probe protective chastity belts?

And then the aliens vanished.

It is possibly of relevance that we were in a massive drought, deeply tired and slightly desperate. It is even more relevant, as I found out later, that in those months the curtains of the aurora australis were visible from this latitude.

But why were we so easily able to believe – or at least not make fun of a belief – that we were being visited by aliens?

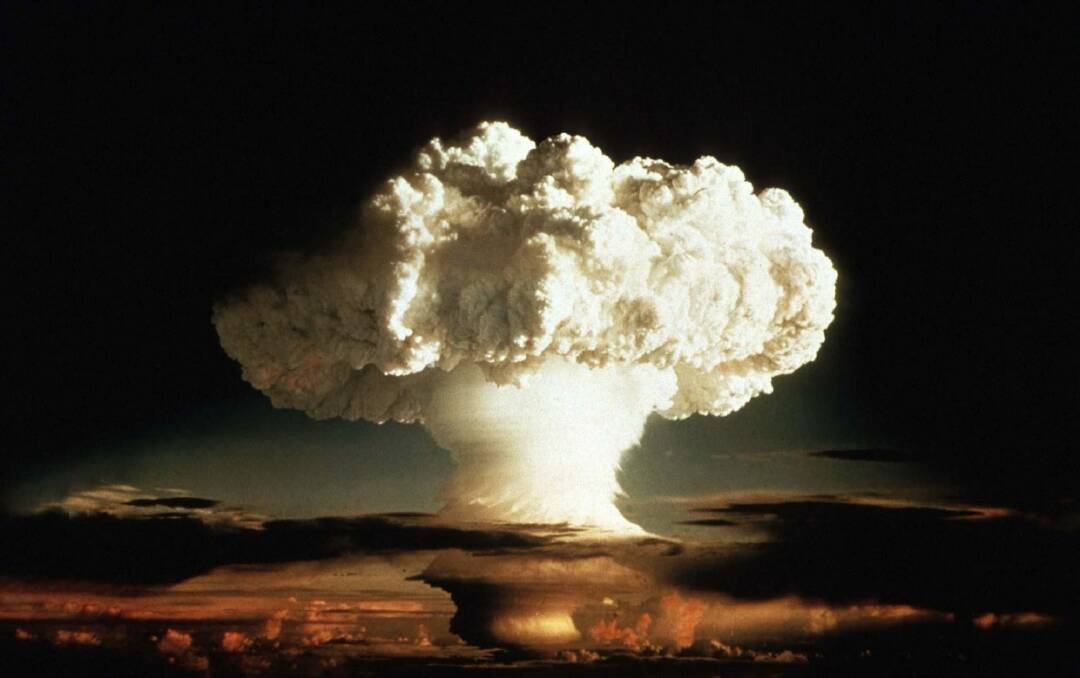

A hundred years earlier, those lights would probably have been taken for fairy dances. But from the 1950s to the mid-1980s, our society was both fascinated by the speed of technological change and frightened of it. This was the technology that gave us TV. It also gave us the bomb. We even had atomic-bomb practice at primary school, hiding under our desks when the siren went, which would have been extremely useful during an atomic catastrophe. At least our corpses would have been neatly laid out.

And then, in the mid-1980s, a new terror emerged. Vampires! The vampires of the 1980s and '90s were sexy, wealthy and powerful. Just like the powerful "new rich".

This was the age of flash, dazzle, conspicuous consumption, leopard skin, limousines and melon-sized new breasts. And it was frightening, if you stopped the dance to think about it, as that was also the era where the limits to growth were being propounded, too; the realisation that we couldn't keep increasing consumption forever. Look at the newspapers back then and you'll see front page after page of our secret fears: the rich who were cheating, lying, manipulating themselves into power and wealth, bottom-of-the-harbour schemes, convenient lapses of memory, too-good-to-be-true get-rich-quick schemes from complex and sophisticated to plain stupid. Secretly, we knew they were our vampires. And they were out to get us.

And now, zombies. Not singly but in hordes, marching, individually weak, tattered, decaying almost to non-existence, but together they can destroy our world.

They are our secret fear, the ones we try not to look at. Like the hordes of the newly unemployed, from industries that were deemed indestructible and eternal only years before, like the car industry, here and in the United States.

In America, whole communities were built on industries that are no longer there. They are inhabited by those who were once confident home owners, swimming-pool owners, three-car families with a TV in every room.

Suddenly, those comfortable lives no longer exist. They probably never will exist again, despite Donald Trump's promises. Industries rarely re-emerge once they vanish, either to other countries with cheaper labour or, even more commonly, are made redundant by new technologies and automation. New industries can and will emerge ... but those lives will not. Could we become them?

Even those whose lives are still comfortable feel excluded from the knowledge class that runs the high-tech world we live in, and the power and wealth that comes from it.

Night after night, too, we see images of the vast tides of dispossessed: the homeless moved away from city streets; the farmers whose land is resumed for mining; the communities who must live with pollution because no company or government will admit that the pollution exists and must be cleaned up, no matter how many kids suffer mental impairment; the Indigenous communities denied our privileges.

We see refugees, desperate, hungry, frightened, needy. They want what we have and to be where we are – in houses, in streets, away from bombs and shrapnel, going to school, lining up to catch buses and trains to go to work, coming home to the smell of cooking, the glow of electric lights and the reality of clean running water. And we really are frightened.

And so we have zombies in our movies and our books. They represent what our society is more scared of now.

And we have reason to be, not just because the growing number of dispossessed may threaten us physically or politically.

We should be scared. Because, by doing nothing, the problems spread. And we may become the zombies.

Jackie French is a children's author and gardening writer.

Facebook: authorjackiefrench

Twitter: @jackie_french_