A fishing spot on the Brisbane Water north of Sydney frames the span of essays in Night Fishing. The spot, known locally as The Hole, is 37 metres deep. While Vicki Hastrich's father would sometimes fish there, she was never taken to The Hole as a child. It was treacherous and known for its huge tidal forces.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

As an adult, and after a fruitless day out on the water, she and her brother decide to try fishing at The Hole, still mindful of that childhood prohibition. What she catches for us in this collection - just like the enormous flathead she brings up after finally fishing The Hole - is surprising and immensely satisfying.

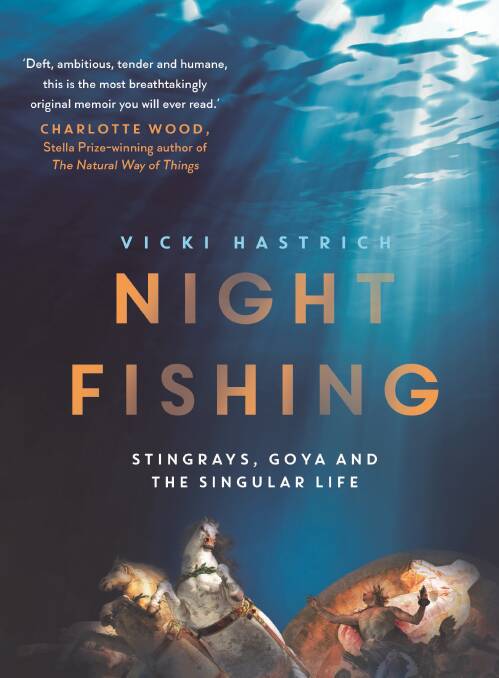

The topics in Night Fishing range over the natural world, art and art history, fishing, family, writing, language, the Sydney boat show, the baroque and the troubled history of land ownership in this country. Hastrich has a unique knack of deftly balancing European, Australian and Indigenous thinking, and rendering each in complementary ways. So there's a pleasingly rounded and very Australian sensibility to her inquiry in this joyful book.

Underlying all of Hastrich's essays are twin concerns: the first is a constant puzzling over what we see, how we see it and how we frame or make sense of that. The second is an insistent desire to understand as best we can, and acknowledge fittingly the natural world around us. The wryly-titled "The History of Lawn Mowing" moves from the life of the late writer Georgia Blain, to an interview with the matriarch of a settler family in the Southern Highlands, and back to the ground on which the Hastrich holiday house sits. "My home is set on an asbestos-contaminated midden," she says plainly, after parking the mower under the house, on shells too numerous to count. Her honesty about our "fouling of the nest and white despoil" is free of any enervating guilt. Her appraisal contains instead a clear-eyed desire to keep looking, keep pushing and keep examining.

Night Fishing shows Hastrich to be a sharp-eyed chronicler of the natural world. Walking her trusty dinghy, the Squid, out over the low tide one day she comes across her own tracks in the mud from the previous day. Intersecting these are the prints of a large bird. It's a moment which is emblematic of the way Hastrich is constantly serving up "the surprise of the marvellous glimpsed". This is a book full of many such quiet and beautiful moments, rendered in phrasing which is both precise and comfortable, exact and fine. Ageing, success and failure are also examined here. The shadow of an abandoned novel hovers over Night Fishing. With trademark frankness, Hastrich talks about this baroque colonial novel which she slogged over for four years, before realising it had no pulse.

But reading Night Fishing, I had the sense of that larger, more ambitious work shoring up this one, in ways seen and unseen. Similarly, reflections on words and Roget's Thesaurus, or on the birds and marine life she records in a notebook titled Thing Seen, are informed by Western art and Western systems of thinking. She urges Milton, Galileo and Van Gogh to "Come out of your cathedrals and museums and work for me here". They oblige.

A surge of interest in, and revival of Indigenous languages, is noted. The word gurumin comes from the Darkinjung language and means the "shadow of a person". (The motif of that word reappears later in the book when she snaps a picture of her shadow on a sandstone platform on Darkinjung country.) Family are here too, most notably her grandfather Pa, an amateur engineer and self-taught welder. Pa was also an inventor of items such as a hose holders, metal punches, prams and dual-flush cisterns. He emerges as a man of great spirit and courage. Hastrich happily claims the title of amateur from him, and the amateur's spirit of "blind adventurousness".

Less successful for me was her essay "Self-portraits". While the lines of inquiry in this piece had appeared elsewhere in the collection - the life and singular journey of the artist for example - her descriptions of the physical process of making a series of self-portraits felt clunky, and without the quickening impulse visible elsewhere in these essays.

Hastrich's knowledge of Western and the baroque underpin much of the writing in this collection, as she touches on artists from Goya to Tiepolo, Van Gogh to Hockney.

But her beloved Brisbane Water region, its waterways, beaches, bays and escarpments, is perhaps the most vibrant and varied masterwork presented here. She writes of the "pure thing at the heart of art that can't be wholly communicated". The ineffable hangs over the land and waterscapes of the Brisbane Water too. This work is a wonderful homage to that place, and to the life of a writer and artist grounded there.

- Christine Kearney is a Canberra-based writer.