Picture this, dear readers.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

It is almost Christmas and in a cell of a forbidding London prison a melancholy and haggard prisoner, an exile from a sunlit land, looks out through the bars at an iron sky from which a cold drizzle is dribbling.

On the cell's outer windowsill a melancholy and haggard sparrow sits, looking in at the prisoner's rudely furnished room (its only decorations a melancholy and haggard aspidistra in a pot and on the wall a framed, signed photograph of the famous human rights barrister Geoffrey Robertson QC, looking uncharacteristically melancholy and haggard) and thanking its lucky stars for the gift of freedom.

There is a flurry of loud clangings, clankings and key janglings at the cell door and in comes Mr Shadbolt, the heavily-tattooed warder.

"Stand up, 886333!" Shadbolt rasps (for over his 30 years of prison service his voice has eerily taken on the timbre of punitive metal grinding against other punitive metal).

"You've got a visitor."

The small space of 886333's cell door fills with a tall, broad, vaguely bear-shaped figure in a baseball cap. Behind the bear there jostles a small posse of aides, suggesting that the visitor is someone of rank.

The visitor bustles in, his bulky body and bulky, exuberant, rapture-ready personality somehow both actually and figuratively filling the tiny space.

"G'day Julian," the visitor enthuses, extending a ham-like hand.

"I'm Scott Morrison."

I lead a rich fantasy life (as this week's introduction illustrates), my fantasies often tinged with idealism.

It is unimaginable that so supposedly devout a Christian can continue much longer to live a life in which he never says or does the slightest thing in imitation of Jesus.

And so during those few days while our Prime Minister was so mysteriously missing I wondered if he might have made a mercy dash to London to pay an unannounced visit to our Julian Assange.

There, I fantasised, he would assure Assange that as an Australian citizen he, Julian, could rest assured that the fair dinkum Morrison government would do everything in its power to fight his expulsion to the United States and to bring him home to Australia.

"How good is that [this prime ministerial pledge of a fair go]?" I heard the Prime Minister enthuse in my fantasy.

In the days just before the Prime Minister vanished a group of 100 doctors issued an open letter to Australia's Foreign Minister Marise Payne urging that she and her government must lobby, quickly, for imprisoned WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange to be returned home to Australia for urgent medical treatment.

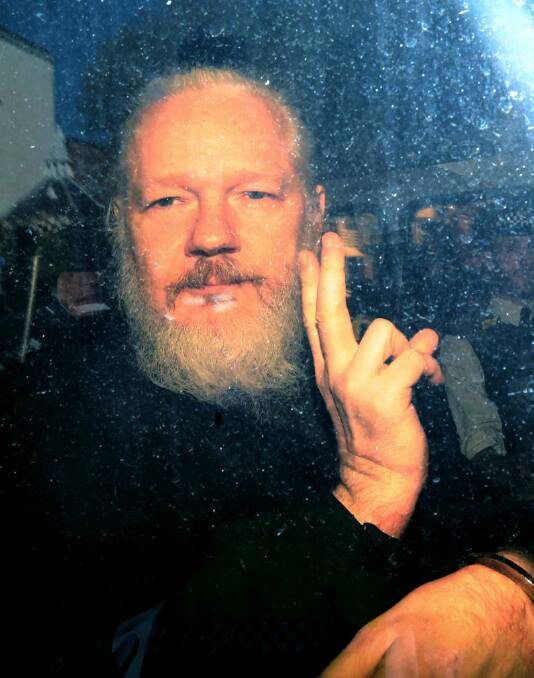

Assange, 48, is said to be in fragile and declining physical and mental health. He is in a London prison awaiting his court fight against extradition to Trump's vengeful US, where he faces 18 charges for "crimes" that some think are not crimes at all.

"Should Mr Assange die in a British prison, people will want to know what you, minister, did to prevent his death," the doctors' letter says.

When I imagined the missing Prime Minister visiting Julian Assange it was because there was a certain logic to it. It is just the kind of Christian, Christmassy, Good King Wenceslassy gesture a devoutly Christian Australian, as Morrison is said to be, must hanker to make. It is unimaginable (isn't it?) that so supposedly devout a Christian can continue much longer to live a life in which he never says or does the slightest thing in imitation of Jesus.

It is not only that Assange's plight (a frail Australian, banged up abroad, fearful of what cruel and unnatural punishments await him if he is transported to raving-mad America for the term of his natural life) must touch every kindly Australian.

No, it is also that the Prime Minister, as a Bible-driven believer, knows where Jesus, his (the Prime Minister's) Lord and Master stands on these sorts of things. The imprisoned were, with all of the wretched of the earth, dear to Our Redeemer's heart.

So for example we find Jesus in his famously forthright Mount of Olives presentation listing a readiness to visit those on prison as a crucial proof of someone's goodness and an essential thing to have on one's CV if one is to have any chance of being admitted to heaven.

I had imagined the Prime Minister, greeted by a ravenously hungry media scrum on his return to Sydney after his top-secret mission to London (of which not a single journalist was informed in advance, not even Michelle Grattan) explaining that there are times when, irrespective of political considerations, a Christian politician must do what Christ has told him to.

I had imagined the Prime Minister telling the milling press at Sydney airport that "Matthew 25: verses 31-40 is unequivocal about all this. As a believer it was my duty to go and see Julian and give him a message of hope."

Then I imagined him declining to answer any more questions (not even Michelle Grattan's) and hurrying away, leaving a bewildered flock of young, scripture-ignorant, post-Christian journalists desperately asking each other who this "Matthew" was and struggling hurriedly to look this mystery figure up in Wikipedia on their iPhones.