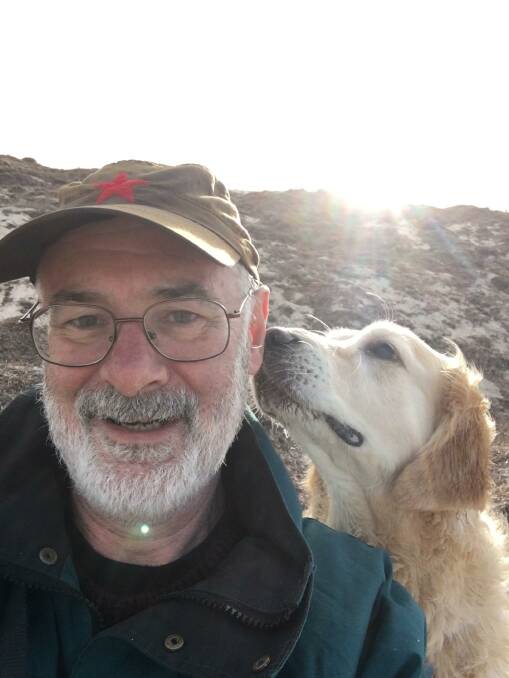

Professer Roger Byard will never forget the name of the first child he autopsied.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

"Genevieve."

Nor will he forget the parents of the children whose bodies he has studied, searching for meaning after the sudden loss of an infant.

Decades of study and experience have lead him to become one of the leading experts in forensic psychology, even earning him a Doctor of Science from the University of Tasmania recently.

It seems fitting that Professor Byard's extraordinary journey started as a child himself, on the Tasmanian north west coast.

"I was just a normal kid in a really lovely country town," he said.

"I grew up in Wynyard. I was very privileged to go to university, neither of my parents went, and not many people in my family had."

The professor graduated from medicine in 1978, and spent the next 40 years collecting more degrees and letters after his name than he can list.

"It's verging on obsessional," he laughed.

"My father said I had a butterfly brain, and he wasn't being complimentary.

"I've just done so many interesting things ... When I discovered forensic pathology I realised how fascinating it was, there are so many unanswered questions and it's so broad."

It turned out to be broad enough to fill over 800 peer reviewed journal articles, three theses and seven textbooks.

Studying the bodies of children who have died too young from SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome) may sound like the worst job in the world, but the Professor's decades of work may have saved thousands of lives.

He admits he loves research, but that having real impact and giving meaning to unexpected death by using it to teach others is more important than a thirst for knowledge.

"That, I think, is how you deal with the sadness," he said.

"It makes the information worth it to think of what good it can do.

"I had a woman phone me, I'd autopsied her child 25 years ago. She wanted to know that it wasn't just another case.

The 65-year-old now lives in Adelaide, and says he can't envision himself retiring any time soon.

"I'm just getting more and more excited," he said.

"I can still make so much of a difference."