I was 12 years old when I first knew something wasn't right," reality TV personality Erin Barnett says.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

"During the weekly grocery shop with my family, I started to feel intense abdominal pain. It was like someone was taking a rusty, serrated knife and trying to hack themselves from the inside out.

"Of course, my mum took me to the doctor, but we were told that it was completely normal. 'Welcome to womanhood,' I remember the male doctor saying, dismissing the pain I was in. Apparently, this was just what having a period was like.

"He assured me that I would grow out of the pain, but as time passed it was clear that wasn't going to happen.

"It took 18 years - and at least 15 doctors - to get a diagnosis and the day I found out I had polycystic ovarian syndrome - also known as PCOS - I found myself crying in the car park not because of what the diagnosis meant, but because I finally had an answer."

PCOS has a lot of different knock-on effects but simply put, it's a hormone imbalance that often - but not always - results in cysts forming on the ovaries. According to the Australian Family Physicians, it affects between 12 and 21 per cent of women of reproductive age, however, up to 70 per cent of women with PCOS remain undiagnosed.

A lot of women don't get diagnosed until they start to struggle to fall pregnant, but for others like Barnett, the knowledge of a family history of PCOS led her to a diagnosis - and the first of 16 pelvic operations - when she was 14.

"My mum and sisters have PCOS so I grew up seeing my older sister on the floor in agony with her period and I used to ask what's wrong, and my mum just said it's because she's just got a period and you'll understand one day," Barnett says.

"I thought that was completely normal and I think we all just grew up thinking it was normal when it's not. And because of that, I think we've just grown up to be tougher as a gender. I think we're way tougher than men."

Despite this family history of the disease, the first trip to the doctors to investigate saw the GP more inclined to believe the then-14-year-old was pregnant before checking for PCOS.

Granted, Barnett's symptoms were not just painful periods. The doctor's visit came after her mum realised how swollen her youngest daughter's stomach had become.

"I lifted my shirt to show [my mum] my stomach and it was bulging on one side and rock hard," she says.

"If my abdomen got that big now, I'd freak out and go to the hospital right away, but back then I just thought I had a fat tummy.

"I used to push it down and try to make it flatter but it was super firm and felt so weird."

After initially examining her, the doctor concluded that Barnett was about 23 weeks pregnant - which the teenager denied. Still, it took three negative pregnancy tests to convince the doctor this wasn't the case.

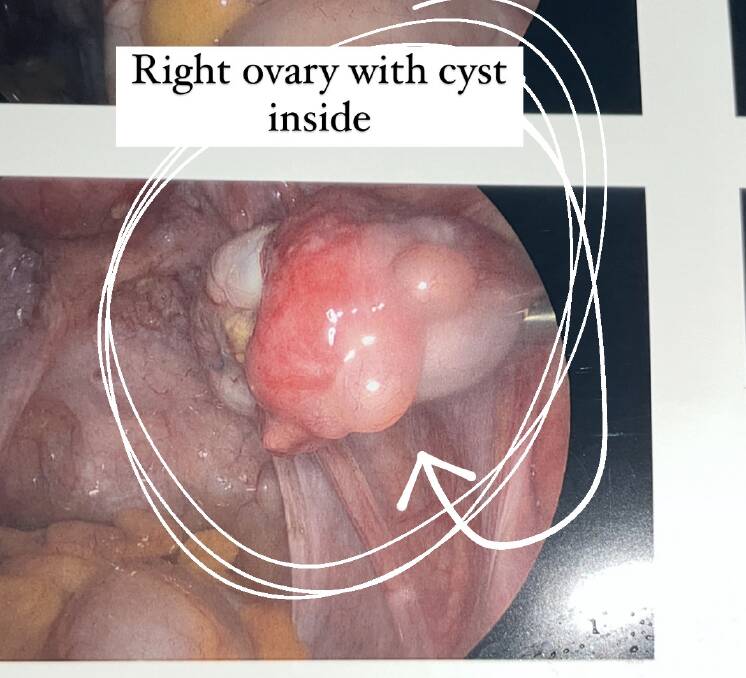

When a scan was eventually taken, it showed a large, three-kilogram cyst on Barnett's ovary. The size of the cyst and Barnett's young age meant the medical team kicked into gear to remove it surgically.

"At the time my PCOS was diagnosed and explained to me, the doctor told me that any future cysts would probably grow on the outside of the ovaries, and they'd usually pop on their own," she says.

"While giving mum and me the run-down, [the doctor] said something along the lines of, 'She won't even notice them most of the time.

"So even though I was aware that I might need surgery when I was older, it definitely didn't sound like PCOS was going to be something that would have much of an impact on my life."

By the time she was 17, Barnett had four more surgeries to remove cysts on her ovaries.

"The first doctor had been wrong: I was only 17 and I was definitely noticing these cysts," Barnett says.

"Having my expectations flipped on their head like this was a shock but there was an upside to it: I was becoming curious and starting to question things."

Among the things that Barnett started to question at this time were the notes taken during one of the surgeries. It was there that she discovered that the doctor saw what looked like endometriosis tissue, but as that surgeon - and the two that followed - didn't take a sample, a diagnosis could not be made.

Endometriosis is a disease where tissue that is very similar to endometrial tissue - the membrane lining the inside of the uterus - grows on the outside of the uterus or other parts of your body.

While there are symptoms, such as painful periods, heavy bleeding and lethargy, the only way you can get diagnosed with endometriosis is by having the tissue surgically removed and tested. According to Endometriosis Australia, it affects one in 10 women and on average, it takes 6.5 years to be diagnosed.

READ MORE:

Barnett was 19 when she was diagnosed with endometriosis - one year after she appeared on Beauty and the Geek, and four years before she would appear on Love Island in 2018.

It's the condition that most of her followers know her for, not just because she details the reality of living with endometriosis and PCOS on social media, but because of how open she was about the disease while appearing on I'm a Celebrity ... Get Me Out of Here! - which she appeared on to raise money for Endometriosis Australia.

The disease also inspired the title of Barnett's new book, Endo Unfiltered: How to take charge of your endometriosis and PCOS.

As well as detailing her journey with the two diseases, the book is a guide to what to expect during diagnosis, what to ask ahead of surgeries, different pain management strategies she has tried, and even how to navigate life and relationships with the diseases.

"When I came out of Love Island that's when it hit me how much endometriosis was going to impact everything," Barnett says.

"At the start of 2019, I had five or six surgeries in one year. And that started to hit me that it seemed to just be getting worse, not getting better. And it wasn't something I had put into my future plan, especially when you're having surgery so many times.

"Some days, I'll recover like two days after and some days I won't recover for like six weeks. And you just become like a hermit at home and that was the moment that I realised, I'd rather take all my organs out than do this every single year."

So far, the majority of Barnett's operations have been to remove cysts, but when she was 24 she had her left ovary removed. Two years later, she then had her left fallopian tube removed.

While she doesn't want to stop there, Barnett has found it difficult to find surgeons who will remove parts of the female reproductive organs. So much so, that when she was diagnosed with adenomyosis in recent months - which is endometriosis that has grown into the uterus' inner muscular wall - it was almost a blessing in disguise, as the only treatment for that is a hysterectomy.

"You know Operation the game? It's just like I'm taking out one thing at a time," the 27-year-old says.

And while she's looking into having her remaining ovary taken out to hopefully help with the pain, Barnett has been told that as long as the ovary is still providing hormones that the body needs, she is too young to get everything removed as it would increase her risk of heart attack and stroke later in life. In the meantime, Barnett has to live in pain.

To demonstrate just how much pain Barnett is in on a regular basis, one of her methods for pain relief is using a searing heat pack or hot water bottle, without a cover. She essentially burns her skin as a distraction from her internal pain.

"The medical industry is always trying to preserve women's ovaries to have a baby. But I want them to put the same amount of effort into helping me be pain-free as they would if I turned around and said, I'd love to bear my own child," she says.

"When it's the other way around, it's 'Oh, no we would rather you be in pain and have two surgeries a year for the rest of your life'.

"So I think the medical industry needs to evolve."

According to the Public Library of Science, endometriosis, PCOS and other pelvic pain cost Australia $6.5 billion every year. The cost for individual women ranges from $16,970 to $20,898.

Barnett says she can easily spend that much every year - and that's not including the money lost from taking time off work due to endometriosis and PCOS.

And yet when it comes to funding, endometriosis research, in particular, only gets a fraction of what other diseases get.

For example, even though a similar number of women suffer from endometriosis as they do diabetes, it only receives 5 per cent of the funding. In addition, in the UK there is five times as much research done into erectile dysfunction - which affects 19 per cent of men - than PMS, which affects 90 per cent of women.

That being said, as the profile of endometriosis has increased in recent years, so has the funding.

The Australian government allocated $15 million to endometriosis research in 2018 and 2019, and in 2020 they allocated another $9.5 million.

It seems the more we talk about it, the more people talk about these diseases, the more funding they get. And that's exactly why Barnett continues to talk about her own experiences.

"It's like my suffering is all worth something now."

- Endo Unfiltered: How to take charge of your endometriosis and PCOS, by Erin Barnett. Murdoch Books. $29.99.

Our journalists work hard to provide local, up-to-date news to the community. This is how you can continue to access our trusted content:

- Bookmark canberratimes.com.au

- Download our app

- Make sure you are signed up for our breaking and regular headlines newsletters

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Instagram