So, have you done the new blockbuster? Performed the customary swish through the latest offering at the National Portrait Gallery? Whizzed through your favourite local gallery on your lunch break?

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

Perhaps you put aside a day or two to peruse the museums in whatever European city you're visiting - all 10 of them.

Perhaps it's time to slow down.

Next Saturday is World Slow Art Day, on which people around the world are encouraged to visit a museum and gallery and look at art slowly. To pause in front of work, and really drink it in. The day is especially targeted at those who believe art may not offer them enough to appreciate. Through slow looking, the theory goes, people might find that art can be appreciated without prior knowledge or expertise, or anything, really, except time and an open mind.

Betty Churcher, for one, is thrilled at the prospect. The former director of the National Gallery of Australia has spent a lifetime looking at art in the most absorbing sense - as an artist, a curator, a director in charge of acquiring works, and, most crucially, as an art lover. Nothing could please her more than the prospect of as many people as possible stopping, if only for a day, to really look at art.

''I really think in this hasty world in which we live, this push-button world, we miss an awful lot,'' she says.

''It's just that fast art swoops into your imagination, but it swoops out just as quickly, and it doesn't encourage you to come back for more and more. And that's the sort of art that I like, that really sits in your memory cells and then demands another look, another think and another angle.''

Churcher has just published her final book about art, a sequel to 2011's Notebooks, in which she travelled to the world's great galleries on a mission - to see her favourite works before her sight deteriorated beyond repair. For Australian Notebooks, she has focused on six major state galleries in Australia. As in Notebooks, the text and illustrations are accompanied by her own annotated sketches of the works, a lifelong habit that has become all the more important as she scrambles to keep the images in her mind even as her eyes let her down.

But, above all, drawing the works as she sees them forces her to slow down and see things she never noticed before. A trained artist, she has an implicit understanding of what she terms the ''engine room'' of the artist - she can look at a work and understand the process of making it. And yet, in the making of this book, she was constantly surprised by the new discoveries she made with almost every work she examined - even those she had been looking at, again and again, for decades.

''They turned out to be a wonderful revelation for me, because you don't get inside the head of the artist until you've got a pencil in your hand, and I made discoveries in pictures that I'd known since I was a schoolgirl,'' she says.

Arthur Streeton's Fire's On, for example, in the Art Gallery of NSW, a painting depicting a mining disaster, is set amid scenery that is so striking and evocative that it's easy to overlook the flames licking the cliff-front, much less the flurry of activity in the background. Look closer, and you will see the miner's family racing down the hill to the scene.

''I'd noticed them but I'd never looked at them properly, and by looking at them properly, I thought that they'd been beautifully drawn,'' Churcher says.

''There's a little woman in a blue skirt hurrying down, holding her skirt up. And one of the things that I'd noticed and never understood until I'd researched it … there's a cart, upended, spilling the dirt back to the tunnel. And I thought, what on earth is that doing? And then I came across a watercolour that Streeton had made before he made the oil painting, before the accident. There's a horse and a cart, and the cart is full of the dirt and debris from the tunnel draft blasting out, pulling it out, loading it onto the cart, carting it away. When the explosion happened and the man was killed, he just let the cart go, the dirt tumbles back and you can see the man on the horse, riding back to the miners' camp. I'd never noticed any of that. It's a narrative!''

She knows this is the case because she has been back to Streeton's letters, in which he wrote to his fellow artists Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin that he had never expected to be painting a disaster. ''He expected he was painting a picture of that lovely sandstone cliff and the tunnel going through. The disaster happened while he was sitting there,'' she says.

She also, in the process of researching the book, was struck, not for the first time but never more forcefully, by what she calls the ''fallacy of selection by committee''.

Roberts' Shearing the Rams, one of the great works in the National Gallery of Victoria, was originally turned down by the gallery's director and board in the 1890s, and went instead to a stock and station agent. The gallery didn't acquire it until after Roberts' death, in 1932. Even a casual glance at the painting makes you wonder what the board were thinking.

Look closer, and you might notice that one of the boys in the painting is looking at the viewer and grinning while the surrounding men and boys toil away. This, says Churcher, is because the boy is in fact a girl, Susan Davis, whom Roberts paid to stand in as a tar-boy. With her hair tucked under her hat, she's obviously enjoying the novelty of being in an area normally off limits to girls.

With a strict limit on how many works she could choose from each gallery, making a selection was difficult; Churcher chose works that were either personally significant, or remarkable acquisitions, both in terms of the institution and the genesis of the work.

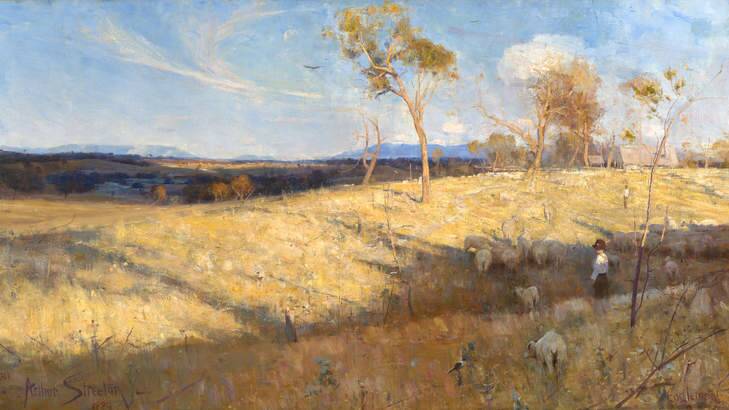

Streeton's Golden Summer, Eaglemont, at the National Gallery, was an opportunity to explain where such artists fit into the canon:

''I think to call the Australian artists of the 19th century Australian impressionists is a big mistake.''

She says a more accurate name for artists like Streeton, Roberts and McCubbin is the Heidelberg School, named for the homestead at Eaglemont, overlooking the hills where they worked from 1889.

''Fred Williams had given the National Gallery a tiny little Charles Conder picture of the inside of that house, and Conder has written along the bottom 'Impressionists' Camp', so we know they liked to think of themselves as impressionists, but I don't think they were,'' she says.

''But the interesting thing is, pinned to the wall of this little, tiny picture, you can see Streeton has pinned a study for Golden Summer.''

Of course, the artist couldn't have known that the gallery would one day own the real Golden Summer, another painting - drenched in light, and the nostalgia of summer - that is worth a good long look.

Ultimately, she says, most artworks have a narrative: ''My whole aim is to try and get people interested enough to look at art, because then they'll make their own narratives,'' she says.

And on Slow Art Day next weekend, Churcher says Canberrans could do worse than stand in the room devoted to Sidney Nolan's Ned Kelly series: ''They're all up there, 27 of them in that room, and what they want to look at is not the story, but the landscape.''

■ Australian Notebooks, by Betty Churcher, is published by Melbourne University Publishing (2014, $44.99).

■ Betty Churcher will be talking about her book as part of the Canberra Times/ANU Meet the Author series on April 24, Manning Clark Theatre 1, ANU, at 6pm. Free. Bookings essential at events@anu.edu.au or on 6125 8415.

■ Slow Art Day is April 12, with events at the Australian War Memorial, the National Gallery of Australia, the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of Australia. slowartday.com.