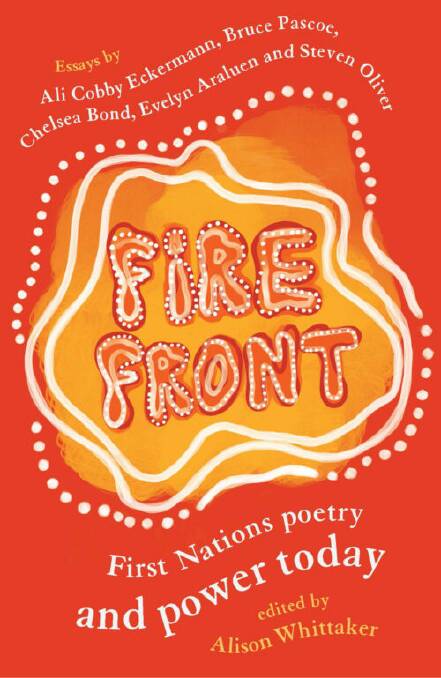

- Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today, edited by Alison Whittaker. University of Queensland Press. $24.99.

It's been 32 years since Kevin Gilbert's important Penguin anthology, Inside Black Australia. With the possible exception of the poetry in Peter Minter's and Anita Heiss's Macquarie PEN Anthology of Aboriginal Literature, this new anthology, edited by Alison Whittaker, is the most ambitious attempt to update and/or replace Gilbert's original.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

The 53 poems collected in Fire Front burn with various ferocities, some more effectively than others in advancing the editor's explicit ambition, "the emancipation of First Nations". Alison Whittaker, a Gomeroi poet and academic from Gunnedah, NSW, has arranged the poems into five thematic sections and invited a well-known Indigenous thinker to introduce each one. They are Bruce Pascoe, Ali Cobby Eckermann, Chelsea Bond, Evelyn Araluen and Steven Oliver. Often what they have to say is at least as cogent as the poems they (sometimes tangentially) introduce.

Pascoe's prose evocation of the ignorant destruction of the elaborate intellectual world which confronted early white "settlers" is particularly moving. He goes on to wonder whether the relatively marginalised art of poetry will ever be enough to effect some sort of restitution. "Are there enough readers left to make it more than a bleat beneath a blanket? Do we use it to hurt those who have hurt us or can we use it to sew up the old possum skin of restraint and civility?"

Steven Oliver, the actor and comedian, addresses the book's mainstream readers directly: "We have been trying for hundreds of years to show you who we are, but all you do is see what we are not: you. We're not telling you to only see us - we're only saying to see you within us. That's connectedness."

Most of the poetry here is from relatively young poets but the poems by Kevin Gilbert, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Jack Davis and Lionel Fogarty are enough to remind us that there is already a substantial tradition of Aboriginal poetry in English.

Inevitably, most of the poetry is "political", just as Ooodgeroo Noonuccal's was back in 1964 when, as Kath Walker, she first published We Are Going. Back then she described her poetry, unapologetically, as "sloganistic, civil-rightish, plain and simple".

Despite a few advances for Aboriginal people since that time, their situation now (shorter life spans, over-incarceration, deaths in custody, children being taken away etc) is still dire. It's not surprising then that quite a number of poems in this book still fit Oodgeroo's 1960s description. Sadly, 60 years of this poetic strategy have not appreciably changed the situation.

Of course, that could be the fault of poetry as a form. W.H. Auden famously wrote "Poetry makes nothing happen". Perhaps a poetry that emphasises the essential humanity of Aboriginal people, and the uniqueness of many of their perspectives, may stand a better chance.

Most non-Indigenous Australians, for instance, know that the Aboriginal connection to land is much more intense than their own (which is not inconsiderable even so) but it's more than useful to have this connection evoked as convincingly as Claire G. Coleman does here in the opening stanza of her poem, "I am the road" : "My grandfather was the bush, the coast, salmon gums, hakeas, blue-grey banksias / Wind-whipped water, tea-black estuaries, sun on grey stone / My grandfather was born on Country, was buried on Country / His bones are Country / I am the road".

The older, more familiar "sloganistic" approach can be seen in a few lines from Elizabeth Jarrett's explicit and hortatory "Invasion Day": "For realise we are still still still / Prisoners of war / Two hundred and twenty-nine years / Of terrorism on our shores / So on today we stand strong together / We have survived / We're black / We're proud / We're strong / And we're alive".

Fortunately, many of the poems in Fire Front are more subtle than this - and, one might therefore argue, more effective. Among them would be "Djwurruwurru: Millad Mob Da Best", a celebration of the people of Booroloola's loving involvement with rodeo (co-written with their friend, the white poet Phillip Hall). It joyously highlights many local words and supplies a glossary translating them.

Another successfully indirect approach is seen in Natalie Harkins' "found" poem, "Domestic", which samples and cuts up the stupidly racist comments of white women in the 1920s "employing" Aboriginal girls in "domestic service". One sentence must suffice: "they were both fearsomely like baboons even to their hairy faces and short thick necks but as waitresses they could not have been better and their laundry work was excellent (1927)"

The 53 poems in Fire Front do much to illustrate the variety of contemporary Aboriginal poetry in English. Strangely, however, the overall levels of artistry displayed tend to be below the technical accomplishment seen so clearly in the work of Aboriginal actors such as Aaron Pedersen, Leah Purcell and Deborah Mailman, or Aboriginal film makers such as Rachel Perkins, Ivan Sen and Warwick Thornton. For those who love poetry, it's sad to wonder why this should be so.

- Geoff Page is a Canberra poet.