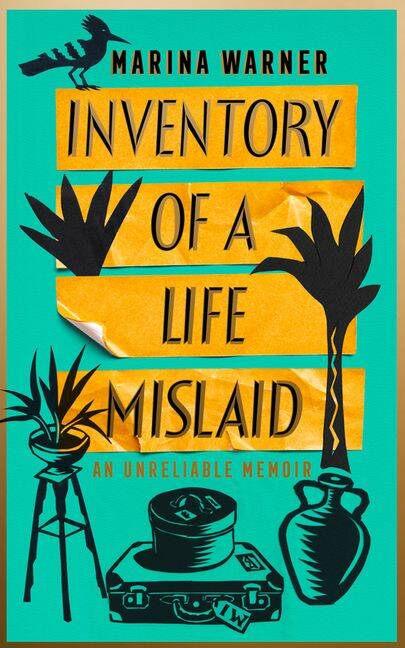

- Inventory of a Life Mislaid: An Unreliable Memoir, by Marina Warner. HarperCollins, $32.99.

Dame Marina Warner has written that her stories often "come from the past but speak to the present". Inventory of a Life Mislaid, which she terms an "unreliable memoir", telling the story of her parents and her early life, certainly falls into that category.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Warner has said the book started as a novel but she changed her mind, adopting an "inventory" approach through inherited family objects, supplemented by her own early memories. The resulting book, she says is "the most exposed I have ever been in my writing".

Marina Warner was born in 1946 into an upper-class English family. Her grandfather was the famous English cricketer and administrator, Sir Pelham 'Plum' Warner. Her grandmother, Agnes Blythe, a Gilbey gin heiress, was rather strangely, but affectionately, known in the family, as "Mother Rat". Warner reflects that Plum and Agnes "were the Posh and Becks of their day".

Her father Esmond, educated at Eton and Oxford, often cash-strapped, never really settled at any job. His life was "a narrow anchorage of cards and cricket, the school yard, the officers' mess, the house party, the supper club".

A wartime romance in Italy saw Esmond marrying the 15-years-younger, tall, beautiful Ilia Terzulli from an impoverished Bari family. With Esmond still on war duties, Ilia, at the age of 23, moved from Italy to live with her parents-in-law in a South Kensington mansion flat imbued with "the smell of England ... suet and soot, cabbage and cabbage water, Worcestershire Sauce, lard, mustard, Marmite, chicory coffee".

Warner's title, "A Life Mislaid", is a reference to Ilia. It was not easy for Ilia to fit into the socially restrictive post-war Britain. Ilia was aware that people "knew she was the youngest daughter of a widow of no means from a stricken region of a defeated nation and a vainglorious regime". She had to learn English social niceties and was even given a cricket bat by Plum, who told her, "there are only two rules in life. Keep a straight back. And your eye on the ball."

Ilia also had to dress the part. Her cork-heeled Italian sandals were replaced with an expensive pair of custom-made brogues, as worn by the young princesses Elizabeth and Margaret; "the brogues would plant her on . . . British soil".

They left British soil when Esmond was appointed, in 1947, through an "old chums" network, manager of WH Smith's Egyptian book sales. Esmond was oblivious to the threats of nationalism - "the Egyptians cannot do without us and our professors, our technicians or our books". King Faruq was still on the throne and Egypt hosted the largest British army base outside the UK.

With servants, a nanny and a cook, the Warner marriage initially flourished in the glamorous, hedonistic Cairo social milieu. Esmond's drinking, his financial problems, their difference in age and cultural backgrounds, however, placed a major strain on the marriage. Warner notes that Esmond's rages turned "a husband into a werewolf". Later, Warner "resolved never ever to depend on a husband".

Ilia and Esmond's relationship worsened when they had to return to England after the Egyptian insurrection of 1952, in which many buildings were destroyed. Visiting the smoking ruins of the WH Smith bookshop is one of Marina's earliest memories. Esmond, who wrote, "I shall never be the same man again", died in 1982 and Ilia in 2008.

Warner recalls clearing her mother's house: "I had lots of shocks. I knew my mother was unhappy - I've known since I was a child. But I never knew the extent of it. It was very upsetting. I found traces of relationships, though I have no idea how far they went. I don't feel angry about it at all, though I know some people feel angry with their mothers for their infidelities."

Warner's sympathies are clearly with her mother. She resurrects her family's life by spinning off objects, such as Ilia's diamond wedding ring, her brogues, a powder compact, an Egyptian cigarette tin, her father's Box Brownie camera and a film cylinder of the 1952 Cairo riots.

Warner says, "I am trying to be her shabti and answer to her ever- present ghost". Here, Warner is reflecting on the Egyptian funerary figurines buried with pharaohs and queens, who were intended to act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife. Warner, beautifully and subtly, has contextualised her parents in a memoir that brings her relief as well as sadness.

The Pelham fortune had "long deep roots" in the British slave trade. Warner has said that "I have been writing throughout my life in response to this background". As she moves through the shadows of her family's history, Warner now reflects, post Brexit, that the "self-assurance about how we (Britain) will dominate the global networks again with trade is very pre-Suez". Stories from the past thus resonate in the present.