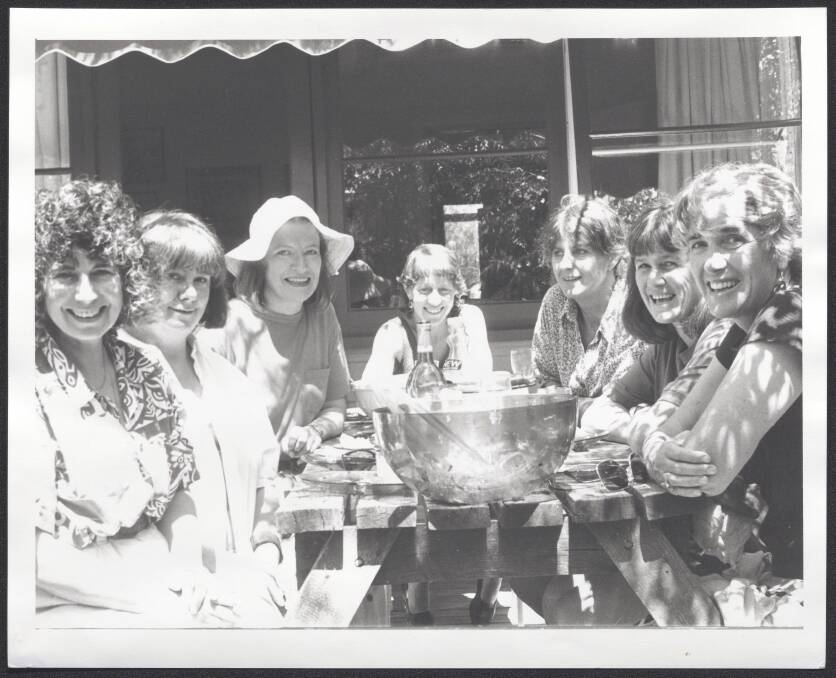

One would prepare lunch. One would distribute a manuscript. And all seven would discuss.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

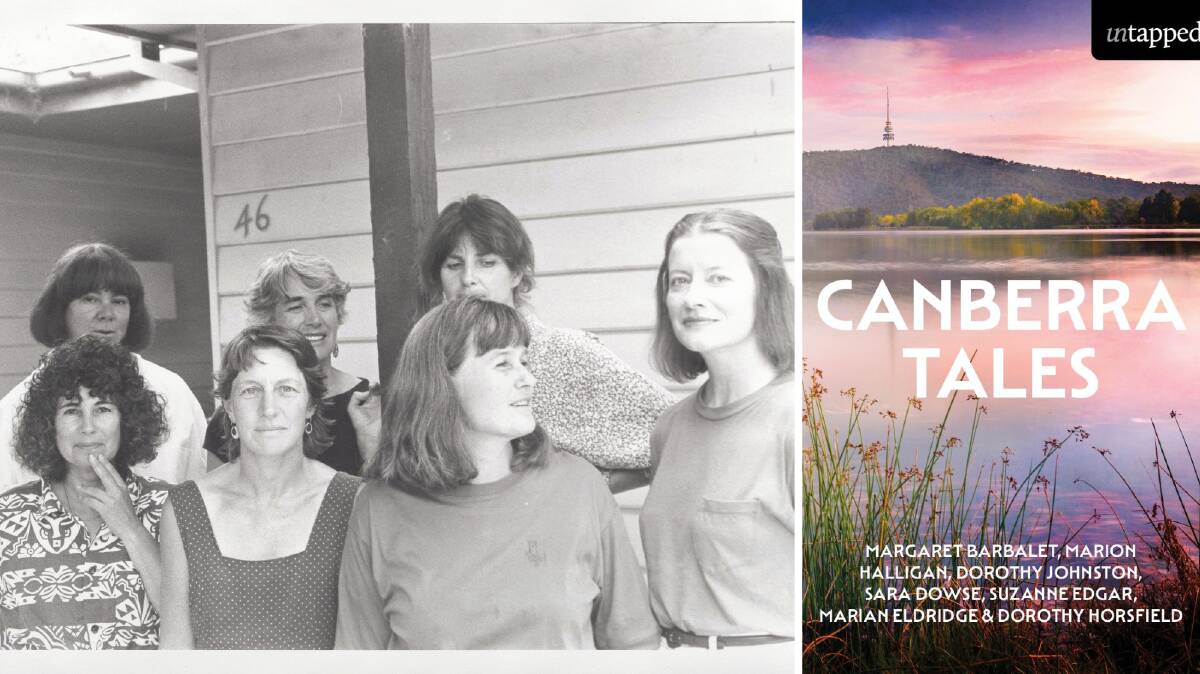

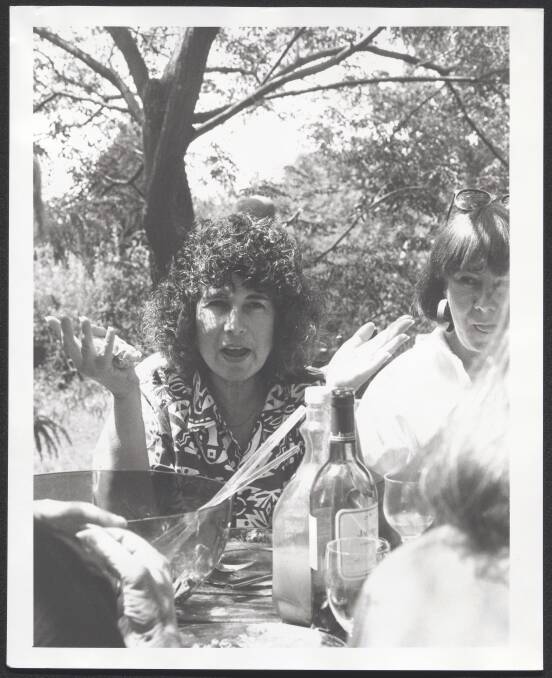

There was a long stretch - more than 15 years - where every month this group of women would meet at each other's homes in Canberra to talk about their writing and to share hints, contacts and commiserations at the inevitable rejection slips. The conversations were robust and animated. Not every suggestion was welcomed. But the group - dubbed Seven Writers - left a significant mark on the literary life of the capital.

"I think there was a decade between the youngest and the oldest. ... That meant we were all going through some of life's big changes at the same time. And I think that it's a hard thing to keep a group going. We went for a very long time, really, as a writers group," says Margaret Barbalet.

"I've always thought that if it was seven men, it would have been a sensation. Because of seven women, it was perhaps not given as much attention as it deserved."

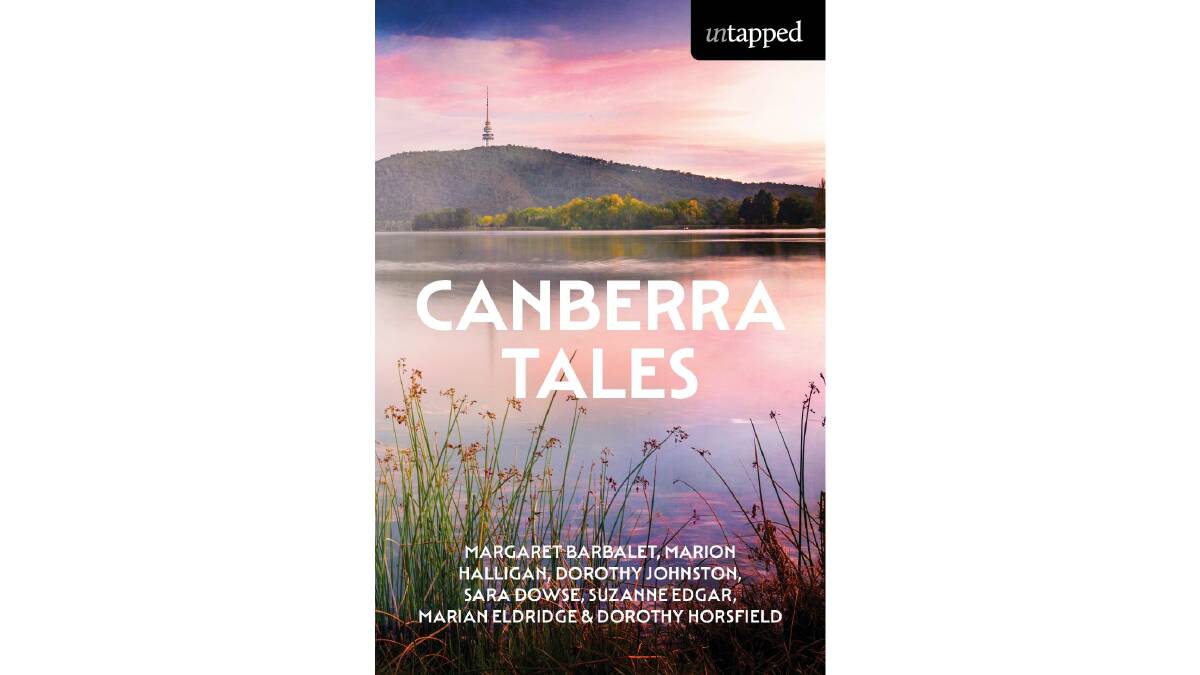

The group was formed in March 1980 and published, eight years later, an anthology of short stories: Canberra Tales. The title - a deliberate, but often missed, allusion to Chaucer's Canterbury Tales - did not sit well with the original publisher, Penguin. Mentioning the name of the national capital, the publishers thought, would be the kiss of death, several of the group's members recall.

The anthology of stories is like a time capsule of late-80s Canberra: New Parliament House is under construction in a city where the hypodermic needle-like tower on Black Mountain pierces a taught sky. The stories are of people coming to Canberra, of shaping lives in the shadow of the institutions of the nation, of finding meaning in a city derided and dismissed by those outside it.

The Untapped project - which makes Australian writing accessible to new readers by digitising books and releasing them as ebooks - republished the Tales, almost three-and-a-half decades since they first appeared: a reminder to a new generation of Canberra's literary pedigree.

Then the popularity of the Tales as an ebook encouraged Brio Books, now an arm of online book retailer Booktopia, to make the book available again in print.

'It gelled into seven'

Seven Writers member Suzanne Edgar says she was astonished when she got to Canberra, where she arrived with her husband in 1963. "I came from Adelaide and I didn't expect to find anything but pretty gardens in this town. In fact, there were more writers and they were more active here than they had been in Adelaide," Edgar says.

Edgar worked on the Australian Dictionary of Biography at the Australian National University, and got to know Margaret Barbalet as she edited Barbalet's contributions.

"I started to write short stories. I don't quite know why I did, but I did, and I was down the beach and I thought, 'I don't really know how to write a short story properly. I think I'll ring up Margaret and get her to look at this thing that I was working on.' And I did that, and we got to be quite good friends," Edgar says.

Edgar says Barbalet invited her to join the group - which was then Dorothy Johnston, Sara Dowse and Barbalet. Edgar says she met Marion Halligan and Marian Eldridge while she was working on Muse, an arts magazine founded in 1980. Halligan and Eldridge were submitting stories to the magazine.

Johnston, who quit a full-time job in 1974 to write fiction, says she, Barbalet and Dowse had wanted a writers group. "We advertised and we initially got quite a few people responding. And so we had these meetings and sometimes it would be four people and sometimes it would be 24, and we were kind of open about it. We just wanted to have a group," Johnston says.

"But then as time passed, it kind of gelled into the seven. We used to meet once a month and that meant you got two proper turns a year to have your own work discussed.

"And then nobody cared or knew in the beginning at all. But then as we started to publish, people started to say we were exclusive and to growl at us and want to join. We sort of said, 'Well, go and set up your own group.'"

Johnston says it was a kind of chance the group came together - and stayed together. None had published more than a handful of stories when they started meeting.

Dorothy Horsfield met Johnston through Johnston's husband, who Horsfield had gone to school with. Horsfield remembers Johnston talking about the group and inviting her to join.

"And, you know, it was an amazingly lucky thing to happen for all of us," Horsfield says.

"I think that we could draw together and help each other - just the sheer joy of meeting a group of people who had very similar literary interests who were well read."

'We weren't always that nice'

Horsfield says she hadn't written fiction before joining the group, which was a springboard to publication. "For me, it was bread and butter going to that group. It wasn't that I learned so much, it's just that I got the confidence to think that I could do it because, you know, I got published very quickly," she says.

"I never had, initially, any rejections whatsoever, which astonished me. And that was immensely important to have this coterie of people around me who just took it for granted that I was dedicated to writing fiction."

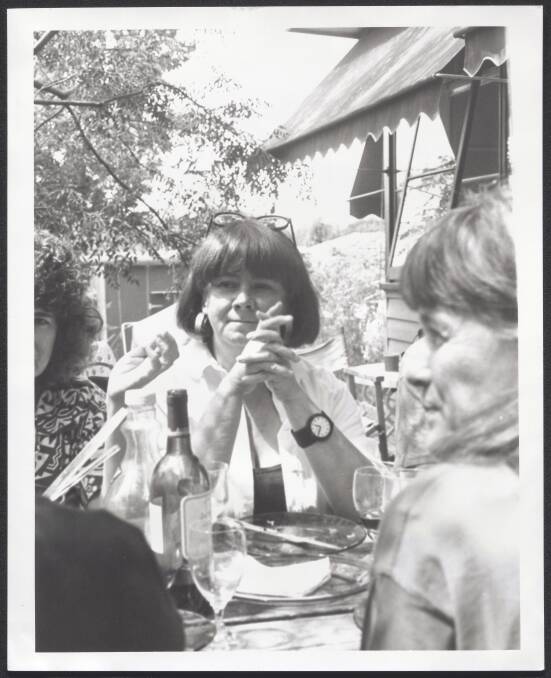

Sara Dowse says the group was more than any creative writing course could have ever been.

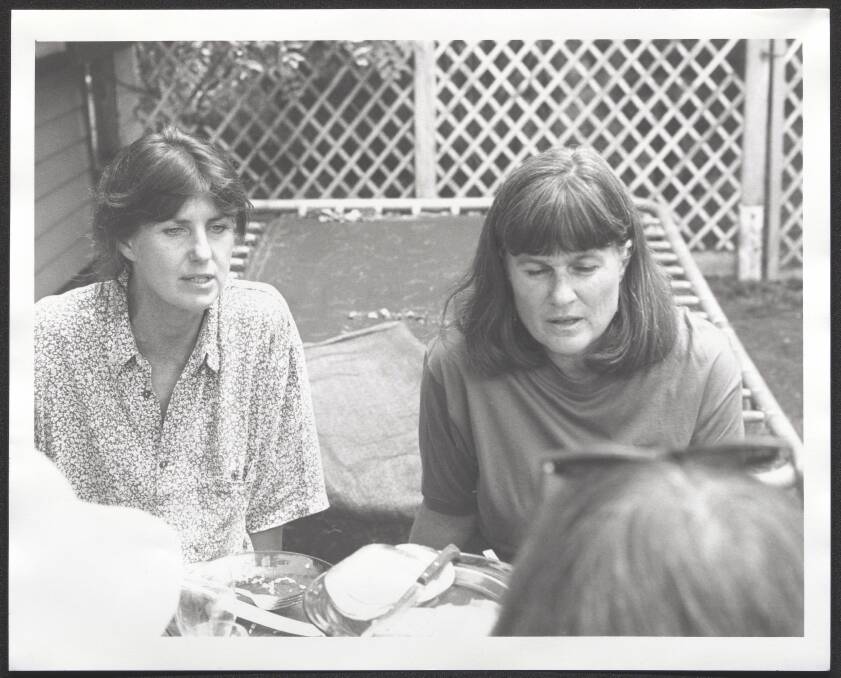

"We were tough with each other, and we were serious about writing. But at the same time, we weren't a school. We accepted each other's different approaches, different themes. I don't think that we could have done any better," she says.

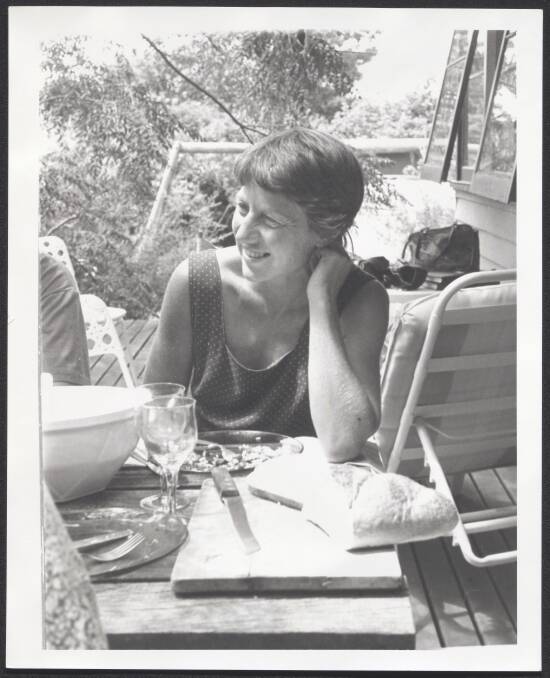

Johnston says the meetings were business-like, held during the day, often on a weekend, because that was an easier time to get help with looking after the children.

"And the meetings were often quite hectic and fiery. We weren't always all that nice to each other," she says.

"We cared very, very much about getting better as writers. Compliments are nice but your family compliments you because they're too scared to do anything else. So a writers' group like ours was meant to do what a family normally didn't do and provide proper discussion."

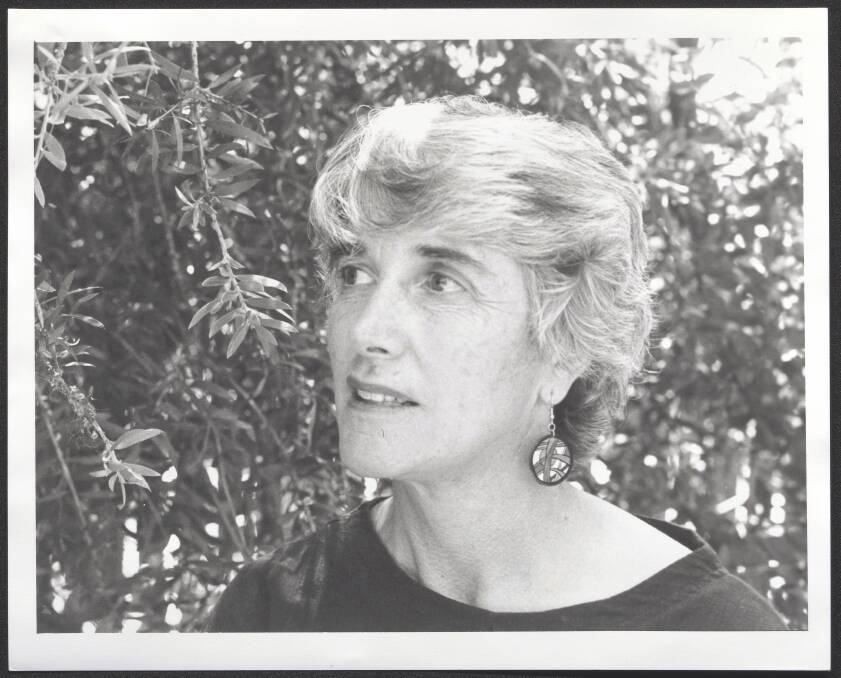

Marion Halligan says the group's meetings were an inspiration to keep going as a writer. "Look, what was important for me was meeting with people who were working, and you'd go and we'd have our meetings on Sunday mornings, and you'd go along and people would be saying, 'Oh, I've done this and I've got this published'," Halligan says.

Halligan says it's possibly become harder for writers working in Canberra now. "Getting published is not easy. I'm still quite impressed when I manage to publish a book," she says.

Sara Dowse says the critiques at the group's meetings could be pretty savage. "But that was OK because we each realised that this was preparation for any sort of response one might get from a publisher," she says.

Chicago-born Dowse arrived in Canberra in 1968, a decade after arriving in Australia. It was an "exciting time", she says, "just when the tremendous political ferment after years of the stodgy, stodgy Liberal-Coalition government, the Menzies years".

After a stint at the Australian Information Service, Dowse joined the Prime Minister's Department. It was an experience that informed her novel West Block (1983), but it was also where she met Brian Johns, a former journalist who would go on to be publishing director at Penguin.

That connection was a lifeline for the Tales project, which was supported with a grant from the Bicentennial Authority. It sold well in Canberra, was reissued as The Division of Love in 1995 and then, as is the path of lots of worthy books, fell out of print. The Seven Writers kept writing though: a string of novels, short stories and poetry.

Johnston says it is important to remember the period of the Tales was when Canberra was developing a sense of itself as a civic body. "I think that was absolutely crucial," she says.

"It was a kind of critical mass situation, if you like, that up until my children's generation, really everyone had come from somewhere else - but that was starting to change and it was changing. And it meant a lot."

'It lost its impetus'

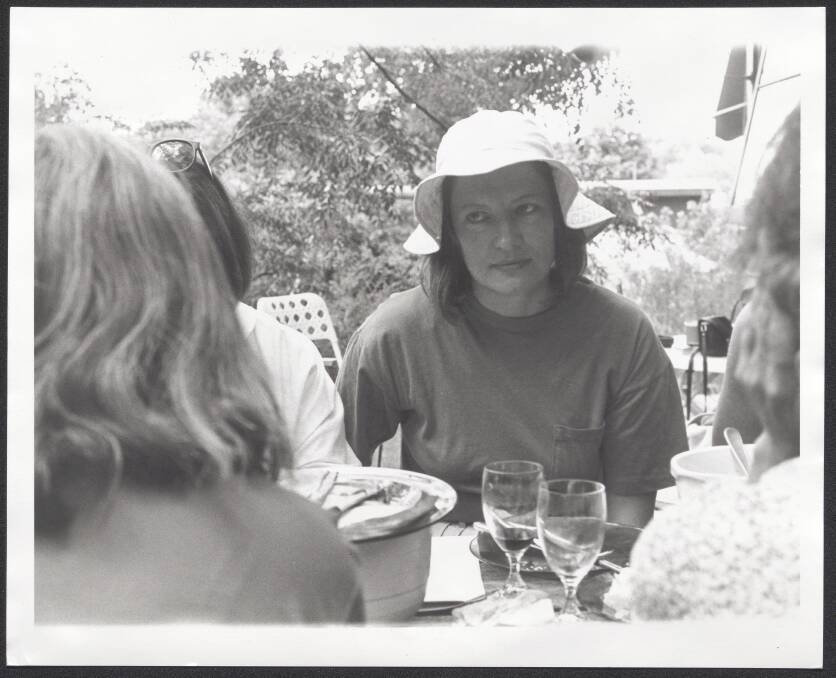

Marian Eldridge died, aged 61, in early 1997. Gone suddenly was a leading figure in Canberra's literary scene, an encourager of young women and writers, and someone who had helped establish the ACT Writers' Centre. Edgar, who wrote Eldridge's obituary, noted she would be irreplaceable among Seven Writers, known for loyalty and integrity, "often reading the material for discussion twice before delivering her wise, thoughtful comments".

Bumpy Favell, Eldridge's daughter and literary executor, says it is an honour to see her mother's work reissued.

"I always assume, I suppose, that people forget and that things from that era, people won't be interested in it. But I have lately been back over the stories, my mum's specifically, and it's like, it's still timely and it's still really delicate and beautiful writing," Favell says.

"And of course the other writers are great too. They're all alive, which is amazing."

Favell, also a writer, says her mother had always been encouraging and it was very devastating she died so young. "Possibly it's not that young, but it was young for her because she'd only just really launched into going to literary festivals and ... all that. She loved that," Favell says.

Dowse says the group met a few times after Eldridge died, but it had lost its impetus.

"And so that was it. But at the time, we were considered to be the longest-running writers' group around," she says.

Horsfield says by the end, the group's members were pretty well established and didn't want the same kind of workshopping. "I think people look back on the group now and they don't really talk too much about its problems, because it had its run and it was a very good thing generally," she says.

Robert Hefner, who served as Canberra Times literary editor for 12 years from 1988, says Canberra Tales made quite the splash when it was released.

"I think it was a very good move to put Canberra in the title because Canberra had a lot of bad press - still does - around the country. It was always a place that was easy to knock: too cold, too many roundabouts, nothing but public servants. The city doesn't have a soul. None of that is true," Hefner says.

"And what Canberra Tales proves, if nothing else, is that there are real people who live in Canberra and they're people with the same kinds of concerns and problems and preoccupations that people everywhere have. And they really stand out in this book.

"I think they put the human face on Canberra."

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.