- The Red Hotel, by Alan Philps. Hachette, $34.99

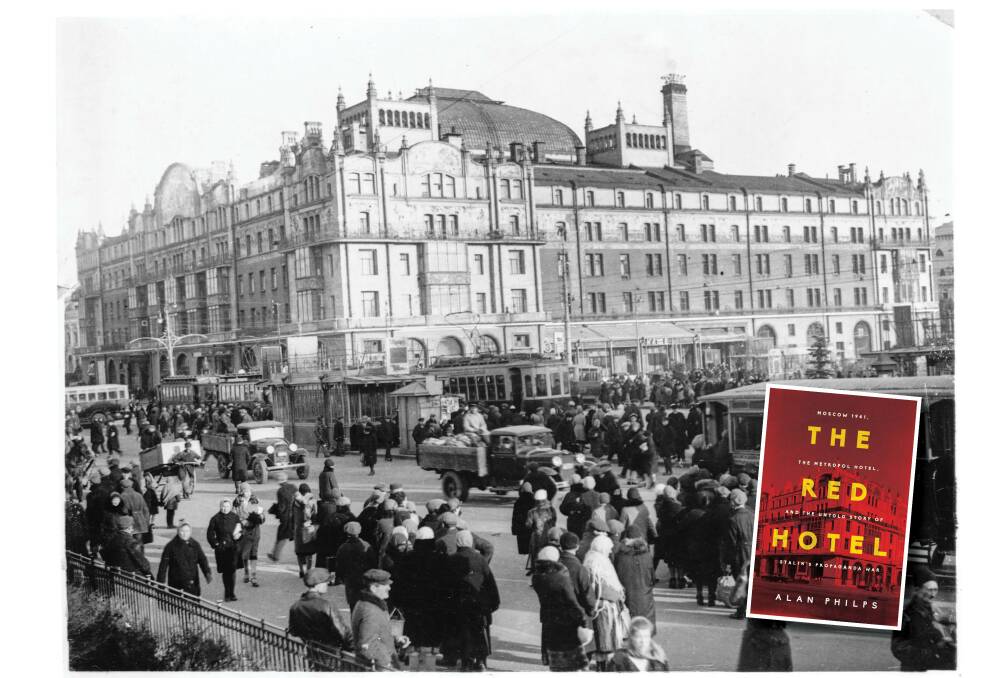

Readers of Amor Towles remarkable novel, A Gentleman in Moscow, may be delighted to know that the hotel they came to know intimately, the Metropol, is front and centre in this book too. It became home to the colony of correspondents, largely from Britain and the United States, but also from Australia and elsewhere, reporting on the Second World War once Russia became a firm and vital ally.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Wow, really? readers might think. A journalist reporting on journalists from another age, glorifying them, making them the heroes of their age? Not a bit of it. Imagine being cooped up in a hotel, no matter how luxurious, drinking and eating to excess most nights, never permitted to even wander Moscow, let alone reach the front line with editors at home screaming for something worth publishing.

Each journalist, overwhelmingly male, with a couple of very wonderful exceptions, were given a "translator/secretary" to read the daily Moscow press for them in the hope of a story. That's what it was, no actual on the ground probing and research, just regurgitating what the Russian censors had allowed their own newspapers to print. Could you make a book out of this? Probably not, readers might suspect.

But Alan Philps succeeds brilliantly. It is as strong a condemnation of Stalin's murder, insanity, paranoia and paralysing control, on a personal level, as readers might expect to find anywhere. There are also large question marks over the probity, integrity and basic honesty of many of the journalists Philps discusses.

From day one the journalists were duchessed, too polite a word for the ferociously organised manipulation of some of the eras most seasoned journalists. Unable to question the regime, fearful of their ongoing presence in Moscow, spied on by almost everyone else in the Metropol, routinely lied to, and knowing it, the journalists covered themselves in shame.

Twice the pack is allowed to leave Moscow. Once to visit a "front line" which the war has long left behind. Another to discover the "truth" of the appalling slaughter of thousands of Polish military officers at Katyn forest.

Readers may well ask why human beings do these things to one another.

The journalists are sent off to the Katyn site in a train whose luxury is simply remarkable. Groaning tables with thick, white, heavily starched coverings, white jacketed waiters in profusion, tubs of caviar on each table, vodka in plentiful supplies, champagne permanently chilled in huge ice buckets. One journalist, rollicking in this luxury, looks out the window as the train slows. He sees heavily bandaged, obviously malnourished, starving Russian soldiers trudging the roadway in the opposite direction. He looks away.

The moral perfidy of this will strike the reader powerfully. But there is more. In the background is the ongoing, unremitting Stalin reign of terror against his own people. The young women assigned to assist the journalists begin to be seen as the enemy too. There are fears that they are betraying their country and its revolution.

One of the great achievements of The Red Hotel is to flood the reader with the personal details of these women's lives. Talented, skilled, devoted to the needs of their country in its direst emergency, several of these women are arrested and consigned to long terms in the gulags. Philps highlights and celebrates their courage, resilience and survival.

A deep sigh of relief escapes the entire world when the news of Stalin's death is announced. No more so than from those who had been tortured, deprived of their families, starved and battered for doing the job the Russian authorities insisted that they do. Readers may well ask why human beings do these things to one another. There is, of course, no obvious answer to such a depressing question. No doubt Stalin was in a class of his own. But the people around him enabled and supported his evil.

What is more worrying in the book, however, is the role of the western journalists in Moscow. They take their pampering for granted. They do little work of any meaning, content to spread the lies they are fed, hardly bothering to check before sending off their copy. They fight one another, sometimes physically, they do their hosts' propaganda for them, and they continue to be well paid by their employers and increase their fame.

Readers who know someone contemplating a career in journalism may want to invite that person to read this book. It tells us of a moral vacuum that should shame and depress any who read it.