Indecisive Moments by Ursula K. Frederick and Katie Hayne. COLOUR/BLIND by Sinan Revell. Huw Davies Gallery, PhotoAccess at the Manuka Arts Centre. Until May 22.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Indecisive Moments highlights the work of two artists documenting two very different aspects of our world in highly individual and affective visual languages.

Frederick begins her series of 20 archival inkjet prints with a framed image of a lone early television. It sits discarded on a suburban footpath accompanied by an equally discarded tyre rim (I think?). Both stand as telling reminders of the short lifespan of modern technologies.

The television, the protagonist of the next five large-scale works in the series, is a particularly pointed and forlorn motif, almost poignant in its abandonment. It is an image with a particular "gestalt", a vintage visual grab that is an effective and questioning introduction to the entire series. The framing and the scale of this work (42 by 30 centimetres), aligned with its title – The last cathode ray tube – invests it with an almost ironic iconicity, the latter subtly subverted in the next four works in the series (Glitch #3, #4, #5 and #6).

The four Glitch works are each 43 by 110 centimetres. A "glitch" implies some sort of malfunction in equipment, usually sudden and temporary. Frederick's "Glitches" announce a more permanent "malfunction".

The artist places a discarded television of the same type and vintage seen above on either the left or right side of the overall image. The televisions have been variously dumped by the side of suburban roads or roads in bushland-edging suburbia, and are accompanied by other disused or out-of-date domestic detritus (a child's stroller, garbage bags, for example). Next to each of these, Frederick places a densely pixilated image that loudly celebrates the new. In these clever and visually seductive juxtapositions she simultaneously questions and celebrates the ongoing and insistent drive of technological change that so engages and absorbs the contemporary world.

The artist's astute use of pictorial devices, such as the thrusting diagonal of a suburban road (Glitch #4), as a metaphor for the inexorable "progress" of technology is particularly apt. The central motif of the healthy looking tree in Glitch #3, standing as a mute witness to the battle between old and new technologies, offers not only a glimpse of the natural world in an otherwise overwhelmingly suburban sameness, but is also a playful visual ploy with the inherent abstraction of the (here) left pixilated image.

Signal #1 – #15, the last of Frederick's works, can be read as visual patterns, compelling in their attraction and at once allusive (what reality lies behind these pixels?) and elusive (how much more information do we need?).

Katie Hayne presents nine images (each 33 by 116 centimetres) that document a trip through Europe. She adopts the trope of the historic panorama, an 18th- and 19th-century visual tool (firstly painted, latterly photographed) that allowed places to be portrayed in their totality; a singular view initially used to delineate a place, to point out the topographical and other details of (often) new or newly-settled places.

Hayne's panoramas do not aspire to any condition of objectivity. They are explicitly subjective and, once again, clever comments on the places and people depicted, on the way panoramas historically existed as "manufactured" images, and as expressions of her own experience of time and place and of the translation of that through the photographic medium.

Although the places may be familiar (for example, Florence, Paris, Berlin and London) Hayne knows that each person's experience of them is personal to that individual. So her panoramas adopt the form of a discontinuous narrative with the actual movement through the places depicted being the essential subject matter.

The sometimes vestigial glimpses and idiosyncratic memories that happen once but recur over time are captured but not defined, since definition in a personal sense is not what the artist is seeking. These are experiential images populated with "empty" spaces into which viewers may insert their own experiences or out of which they may capture them again. This is not to say that the artist loses her own imaginative identity in these works. Rather, each image is marked by the strength of her creative and imaginative language and its ability to speak not only to us but take us with it.

Hayne and Frederick know how to construct a potent image and how the parts that form each structure speak to one another within and without the edges of their images.

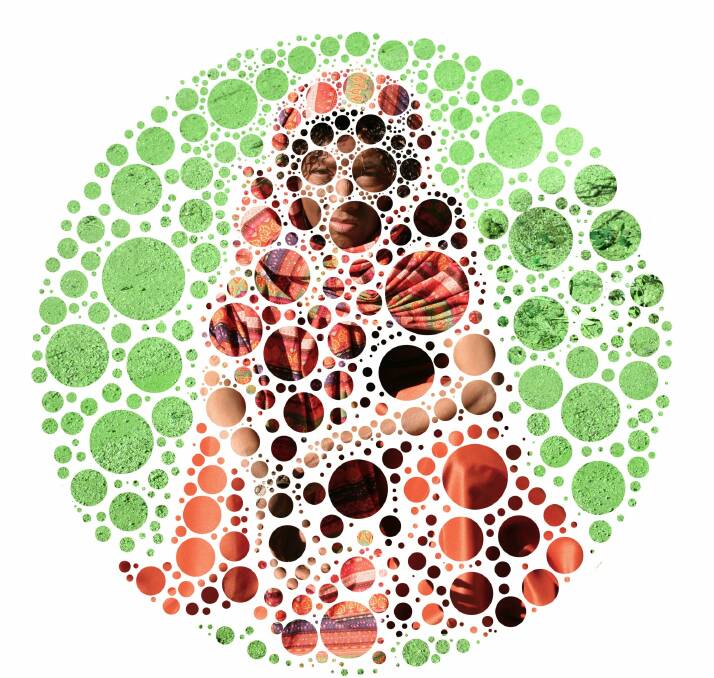

In COLOUR/BLIND, Los-Angeles based Sinan Revell takes the dot matrix used to test for colour blindness as the thematic and visual starting-point for her five works.

The artist is not only the maker but also the "subjects" of her various images. Each work's title is an overt clue to what lies behind the screened vinyl dots that sit above the photographic image (again, archival inkjet prints). So, for example, Elderly shows the face of an elderly woman; Burqa, a woman wearing the ubiquitous Muslim garment; and Refugee a woman from North Africa (?), silently pleading.

By making herself the subject, Revell creates a personal meditation of what and how we see. The artist becomes the disenfranchised women she portrays and while she looks at them/herself, they/she view us through a mediated gaze. The gaze as pictured in a circular format speaks of the controlling lens and, allied with the overlaid dot matrix, speaks more of the need to look critically at the plight of those on the edge and at the images used to depict them.

Self as "other" may be seen as indulgent theatricality but Revell's images contain a seriousness that places them well outside that position. There is a sinister truth in her depiction of the power that lies with those who control how and what we see.