Late in 1976, I returned to Australia after a prolonged stay in Europe. At the time we were expecting our second child and I quickly realised that I could no longer survive on scholarships and was in need of a less itinerant existence.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

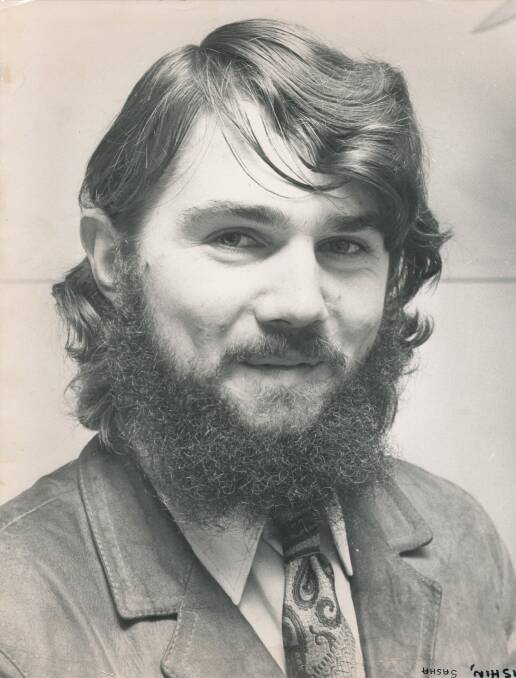

The Australian National University made me an offer that I could not refuse, an invitation to establish the academic discipline of art history at the university on a 0.5 appointment to the Faculty of Arts and a 0.5 appointment as a Visiting Fellow at the Humanities Research Centre. At about the same time, the editor of The Canberra Times, Ian Matthews, phoned me and invited me to be the Senior Art Critic for the paper. All of this was a bit overwhelming for a young bloke in his mid-20s.

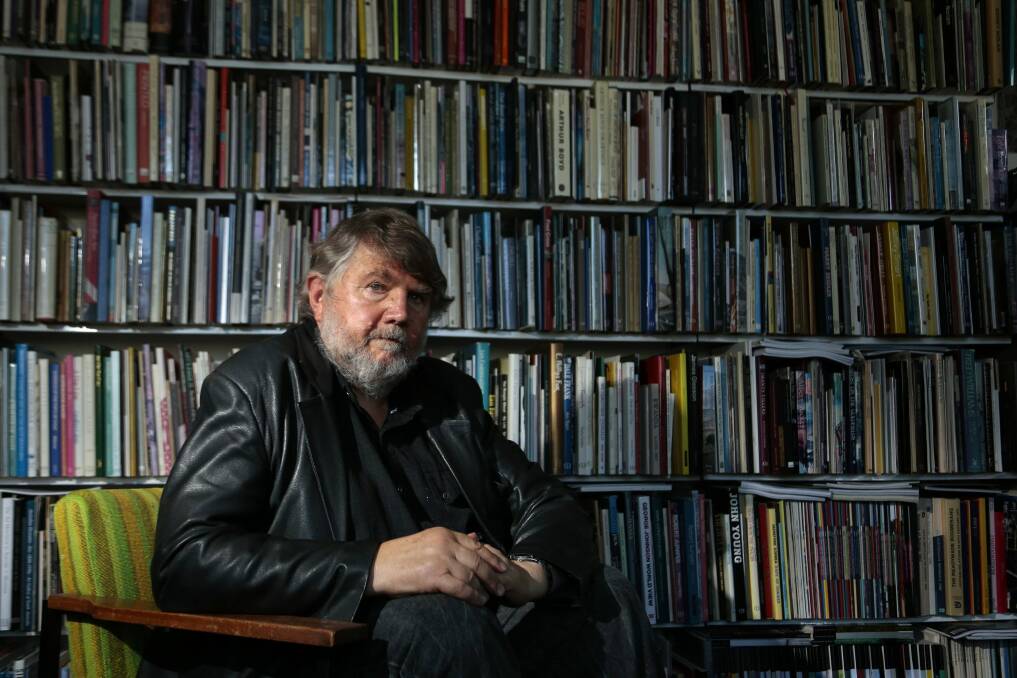

Now, about 40 years and approximately 3000 published art critiques later, it seems timely to reflect on the role of a newspaper art critic in Australia. Before I came to The Canberra Times, I remember once asking the prominent American art critic, Clement Greenberg, a simple question concerning the changing role of an art critic in the modern art scene. It took me a long time to understand his answer: "An art critic writes for an audience that will understand him and one should never forget that an art critic is a person who learns in public." In a newspaper, one does write for a broad educated audience, but over the years I have had a number of battles on just how accessible one's writing needs to be. I remember one frustrated sub-editor pointing out to me that my pieces should be accessible even to those readers who read the paper from the back, and that I should not use, without explanation, terms like surrealism, cubism and impressionism. It took me some time to explain that those people who normally read the paper from the back, would rarely look at the art section and if they were art-loving and sport-loving people at the same time, in other words, people like myself, then they were unlikely to be in need of a glossary of common art terms.

With regards to learning in public, Clem could not have been more on the money as you grapple with many levels of art and learn on the job. After publishing some of my early art crits in 1977, one of my few old friends at the ANU, the poet AD Hope, took me aside and related to me the following anecdote. He said that when he was a young poet in Tasmania, he once savagely reviewed an anthology by a young emerging poet because, in his words, "she was really bad". A little after his review was published, the poet committed suicide and Alec felt maimed for life by the experience. I never did find out if Alec actually invented this "experience" for my benefit, fearing that my early crits were becoming a little too harsh and critical. Subsequently, I have always had this story at the back of my mind when I review the work of emerging artists, deciding at times to say nothing at all, if I could not find anything positive to say. An artist's exhibition is frequently something very precious and intimate and a critic must be aware that he may be treading on someone's dreams.

In the early years of reviewing for The Canberra Times, photographs as illustrations for your words were a rare luxury and you would spend much of your time describing what you saw. It is only in more recent years that photographs have become much more prevalent and today a review would rarely be published without images. Now that the paper is also available online, the online version will frequently carry all of the images that would sometimes be left out of the printed edition.

From my perspective, a critique of an exhibition usually involves two closely interrelated functions. The first could be termed an exegetical function – explaining, interpreting and to some extent re-creating a work of art, an exhibition or the artist's oeuvre. The second is a judicial function – an evaluation, but also creating a perspective within traditions of art history through which to view the exhibition or an artist's work. Where there exist precedents, an earlier evaluation or discourse built up around an artist's work, for example, when looking at the work of Jackson Pollock, Louise Bourgeois or Tom Roberts, a critic's role may involve a re-evaluation of an artist's work in the light of tradition. Does the work appear dated, uninteresting and repetitive, or has it stood the test of time and aged gracefully?

However, much of the art critic's work deals with the experience of contemporary art that is being exhibited for the first time, where there is little or no tradition and you are called upon to understand, explain and evaluate new art to a public completely unfamiliar with it. Art criticism is frequently described as the first draft of art history and it is here, in particular, that the art critic learns in public. On a number of occasions, I have seen work that appeared as fresh, new and amazing and have said so in print and then have never heard of the artist again. On other occasions, work may appear as gimmicky and slick, but the art audiences loved it and it emerged as the next big thing. I was not necessarily wrong, but the art critic's voice is only one ingredient in an artist's success and frequently not the main ingredient.

When I look at art criticism from the perspective of an art historian, I note that in the past there was a plethora of newspapers, all employing art critics. When an exhibition opened a swathe of critiques appeared in the press. In Paris of the Impressionists, there were literally hundreds of newspapers and magazines that maintained a constant art commentary. When looking through artists' clipping files from the 1950s and 1960s, every time there was an exhibition in Melbourne or Sydney, four or five critiques appeared in the press. Now, it is unusual for there to be even a single review in most Australian cities on exhibitions held in nearly all commercial art galleries and commentaries on institutional media releases from the major state art galleries pass for art criticism. Without wishing to sound chauvinistic, Canberra, mainly through The Canberra Times, is better provided for in art criticism and art commentary than any other city in Australia. Canberra is smaller, more intimate, more educated and more "arty" than most Australian cities.

Like all art scenes in Australia, Canberra has changed enormously over the four decades that I have been writing for the paper. In common with most Australian cities, the commercial art gallery sector has largely imploded. If 20 years ago I could easily name 10 significant operating commercial art galleries in Canberra, today there are only a couple. However, where Canberra is different from the other Australian cities is in its national status and in the growth of major national art institutions, as well as the Australian Capital Territory art institutions and the network of publicly-funded artist-run spaces. In 1976 there was the Arts Council, the National Library, the Australian War Memorial plus a few itinerant organisations of artists. Today, starting with the National Gallery, the National Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, it becomes a very long list.

With a population of under 400,000 people, Canberra has more art facilities per capita than any other city in Australia and in this sense can claim to be the nation's art capital. This is where the national visual and cultural heritage is collected, stored, studied and preserved for posterity, which makes the cuts in funding to public art and cultural institutions in Canberra under the present federal government particularly silly and short-sighted. As a long-serving art critic, it has been an exciting privilege to have observed and written on all of these national art institutions.

While I am writing this as a personal reflection, the critics' role in The Canberra Times has always been a team effort across the arts where, on my watch, there have been numerous contributors, some outstanding, who have enriched the discussion and on occasion provoked debate. While there may be no such thing as "objective" criticism, as we all bring with us a lifetime of experience that will inevitably colour our judgements, a good art critic will make the art under discussion accessible to a broader audience. This has been my aim. Back in the 19th century, the great French critic Charles Baudelaire defined the role of an art critic, something with which I still have considerable sympathy: "To be just, that is to say, to justify its existence, criticism should be partial, passionate and political, that is to say, written from an exclusive point of view, but a point of view that opens up the widest horizons."

Sasha Grishin AM, is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University and works internationally as an art historian, art critic and curator.