On a busy road in Queanbeyan, next to a pet shop and opposite a Chinese takeaway, you'd never guess what lies behind the modest terracotta house set back from the road behind a small cluster of evergreens.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

The Curtis Glass Studio is a revelation, a large airy workspace filled with eye-popping objects wrought in coloured glass. Beautiful, complex and fascinating, the place is filled with Matthew Curtis's architectural sculptures and Harriet Schwarzrock's floating glass fronds that seem on the verge of swaying in the slightest breeze. There are shelves stacked with pod-shaped vessels, etched bowls, highly refined experimentations in light, colour and form. It's an office, a hotshop and a studio all in one – a creative space that is constantly evolving.

With two very different styles, the pair work in parallel, producing functional and architectural pieces that, in distinct ways, challenge the boundaries of what glass can do.

Their works are highly regarded in different spheres – Curtis sells most of his pieces to collectors in the United States, and Schwarzrock recently won the sculpture section in the Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize – and the whole practice is woven into their family life, with two boys and two dogs, all moving through a "shifting puzzle" whose creative centre is the warehouse in their own backyard.

This warehouse is the reason these two artists, originally from Sydney, decided to settle in Queanbeyan, of all places, to fulfil their dream of owning and working in their own space.

Married for 15 years, the pair met while Schwarzrock was a student at Sydney College of the Arts, and Curtis – originally from England – was helping the artist Robert Wynne to establish a glass-blowing studio in Sydney. He had no formal training, but his apprenticeship with Wynne led to him establishing his own practice.

Later, with two very young sons, the couple rented a studio space in Sydney and an apartment, when Curtis happened upon this storied – talked about but not yet seen – location in Queanbeyan. A biscuit factory and carpet warehouse in previous incarnations, it had lately been a temporary residence behind a decrepit house that was, quite literally, a drug den.

"I'd driven down to Canberra to buy some equipment, some old equipment from the ANU, and as we were driving past, my colleague said, 'You should check that place out'," Curtis says.

He recalls taking one look at the large space – a ramshackle factory space and a "renovator's dream" of a house – and seeing everything they needed. They bought the property without even seeing all the rooms, and took the plunge into a major renovation project. For the first few months, the young family lived in the studio while they slowly made the house liveable. They knocked out walls, rewired the whole house, and cleared out skip after skip of junk.

That was 11 years ago and today the house is, frankly, gorgeous, a warm, cluttered space filled with colour and glass and art by other people. It's a house that is most adamantly a space to live in, rather than show off, although like all picture-worthy dwellings, it's filled with innovative DIY, junk-shop finds, IKEA and inherited furniture.

But it's the studio that is the piece de resistance. They set it up well before the Canberra Glassworks existed, and have been running a successful creative business ever since. And it's the thing they were most thankful for when the global financial crisis hit a few years ago.

Curtis sells most of his exhibition work to American collectors, in a marketplace that is full of them.

"There's a very big collectors' scene for glass, which is only just sort of developing in Australia," says Schwarzrock.

"It's quite a thing in the States to collect glass, and there are glass collectors, not art collectors who are interested in glass."

But when the economic meltdown came, it didn't take long for the effects to take hold.

"It happened almost overnight and it was quite tough," says Curtis.

The couple scrambled to readjust as a major source of income became shaky. They had been running the studio as a fully fledged business, employing assistants to help Curtis create his large-scale works to be shipped off to art collectors in the US. In any given week, they were employing three or four people to help with steelwork, making crates, or in the hotshop. But when the money stopped coming in, Schwarzrock found herself stepping up to the mark as assistant, something she hadn't done in the past.

"For exhibition work, I often blow components out of the different tints of glass that we melt in the furnace at the end of the sessions, whereas Matt needs a consistent kind of assistant to produce all of the regular components," she says.

"But then, I guess, when that sort of financial thing happened, we shifted our business so that I sort of stepped up and did a lot more production work."

It's obvious throughout the interview that they're an easy-going, affable couple, happy to get on with their own work and see their own ideas play out in parallel. Nevertheless, it came as a mutual surprise that they were able to work well as a team.

"It went beautifully! Harry is wonderful to work with, and hopefully I worked well with her," says Curtis. Schwarzrock responds with an affectionate eye-roll.

These days, the worst seems to have passed, and Curtis, at least, is finally letting himself try new things and develop his craft. He has spent the last two years bending over backwards to give collectors exactly what they want, in the name of keeping his name out there and money in the bank.

On the day of our interview, he's busy preparing to ship off a new body of work to Chicago, as part of his yearly pilgrimage to the Sculptural Art and Functional Objects fair in Chicago, the best way to get their work seen.

"It's very significant for a lot of glass artists because it's such a large event, it brings together a lot of other artists and a lot of gallery directors, museum directors, curators, collectors – all sorts of people come there just because it's such a large event," he says.

"That makes it quite an important focal point during the year if you want to bring some new work, and you get seen by a lot of people."

Curtis recalls travelling there at the end of the first really bad post-GFC year – the ticket had been pre-purchased – after a joint exhibition in Ohio had failed to sell any of his works. The show had been well-populated with reassuring red dots early on, but the climate shifted dramatically with the arrest of Bernie Madoff, infamous perpetuator of a massive Ponzi scheme. The red dots swiftly disappeared.

"I just went well, I'll fly over and we'll show some of this good work at SOFA. And to be honest, I was really quite desperate to just make things happen," he said.

"And as it turned out, my work was viewed in the States as being really quite good value; large work at that scale would usually have a higher price ticket on it."

A significant collector from Florida contacted him about a particular work, haggling over the price, requesting a larger size and commissioning more work. He gave in to every one of her requests, and before long other collectors had started to take notice. It ended up being one of the best years he had had from the SOFA show, but he came back with a pile of commissions for difficult, large-scale work that dominated his time and creative space.

This year, with their heads above water again, he has decided to go against the grain of post-GFC restraint and make exactly what he wants. He also scored a residency at the Canberra Glassworks earlier in the year, allowing him to stretch his wings in a new space and experiment, with plenty of assistance and other artists on hand to help develop ideas.

Schwarzrock usually travels to Chicago to show her own work as well, but is staying back in Canberra this year, with her own projects. She's also still surfing the high of having won in the Waterhouse Prize, her first in such an exhibition, and was also a finalist in the 2014 Hobart Art Prize.

Although she has been making, exhibiting and selling art steadily over the years, her career has never been as established as Curtis's, mainly because she had their two children – Oscar, now 14 and Hugo, 11 – before she had the chance.

"It takes a little bit of doing to bust back in or to get noticed. I think there is a bit of a pathway from doing a degree into the next opportunities or group shows or survey shows," she says.

But as far as Curtis is concerned, this has been Harriet's year.

"I think it's been hard for both of us in different ways, but I think really, in my mind, I see it as a time for more focus on Harry," says Curtis.

"When we started out, building the studio and trying to get things up and going, we had young children and Harry was primary carer there, and just as the kids were old enough to go off to school, and sort themselves out, the GFC hit and that sort of held us back a bit."

At this point, the interview turns into a conversation between the two of them, discussing their work as they probably do all the time.

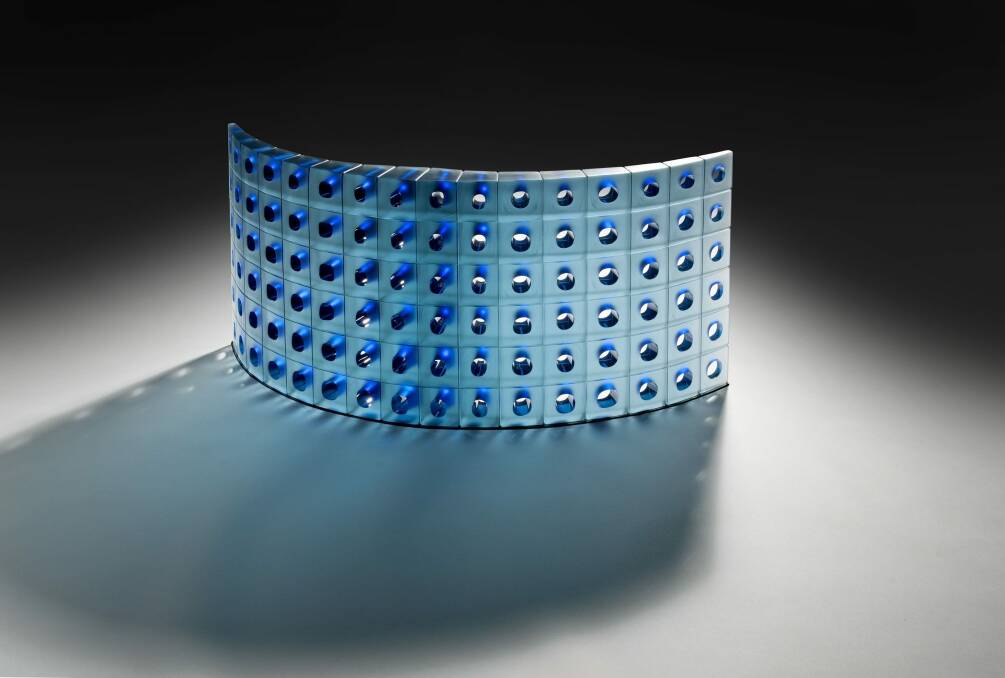

"I think Matt makes quite architectural and structured work. Often the aesthetic or the start of the idea is sort of the architecture of organic structures, and with this last little push that Matt's had, and a bit of playtime at the Glassworks, he's got to develop some ideas that he's been talking about for a long time, based around the hexagon and the beehive kind of structure, which has been really nice to see," Schwarzrock says.

"It's interesting that we both use glass components, and we're inspired by biology and things like that, but we have a very different approach and result," says Curtis.

"[I use] hard lines, and Harriet's pieces are more sympathetic to its neighbour, if you like – the corresponding pieces … It's wonderful for me to see, and it inspires me a bit to sort of loosen up a bit."

Both agree that while there is no competitive element to their relationship, they often test ideas based on the other's reaction.

"You'd laugh at how one of our barometers of how something's going to turn out is how much the other goes, 'Oh, I don't know about that'," says Schwarzrock.

"I think we have to be pretty honest with each other about work – it's good we can do that," Curtis says.

But a joint exhibition isn't on the cards just yet.

"It hasn't been a priority, working out a show together, and it's such an investment of time and resources to make work for a show," Schwarzrock says.

"I think to have an exhibition together, that's both of us putting all of our energy into the same end point, and I think that that would be quite an intense endeavour."

They do each have a work proudly on display in the residence of US Ambassador to Australia John Berry – he and his partner Curtis Yee are huge fans – and will be opening their studio to visitors as part of the Queanbeyan Arts Trail later this month. It's something they've done several times, as a way to stay a part of the local arts community.

As Curtis points out, it's a shame that so much of the work produced in the studio is packed up and sent overseas before anyone here gets to see it. The open studio is an opportunity not only for a clean-up but also to show people what glass can do.

Curtis Glass Studio will be open to the public on Sunday October 26 as part of the Queanbeyan Arts Trail. For more information, visit qcc.nsw.gov.au.

Harriet's Schwarzrock's winning work Breathe is currently on display at the National Archives of Australia, as part of the Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize, which finishes on November 9.