Barry Kirby was a "chippy" on sabbatical in Cairns when a small newspaper ad for a project manager in Papua New Guinea’s Menyamya village caught his eye.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Now more than 20 years later, and after a radical career change, Dr Kirby is helping to change the lives of PNG mothers in a country where one-in-20 die during childbirth.

Even during his early days in PNG, Dr Kirby had thoughts of becoming a doctor to help the villagers he worked alongside in Morobe province.

But after finding a pregnant woman left for dead on the side of the road and taking her to hospital where she later died, Dr Kirby took the plunge to retrain, eventually graduating from university at the age of 50.

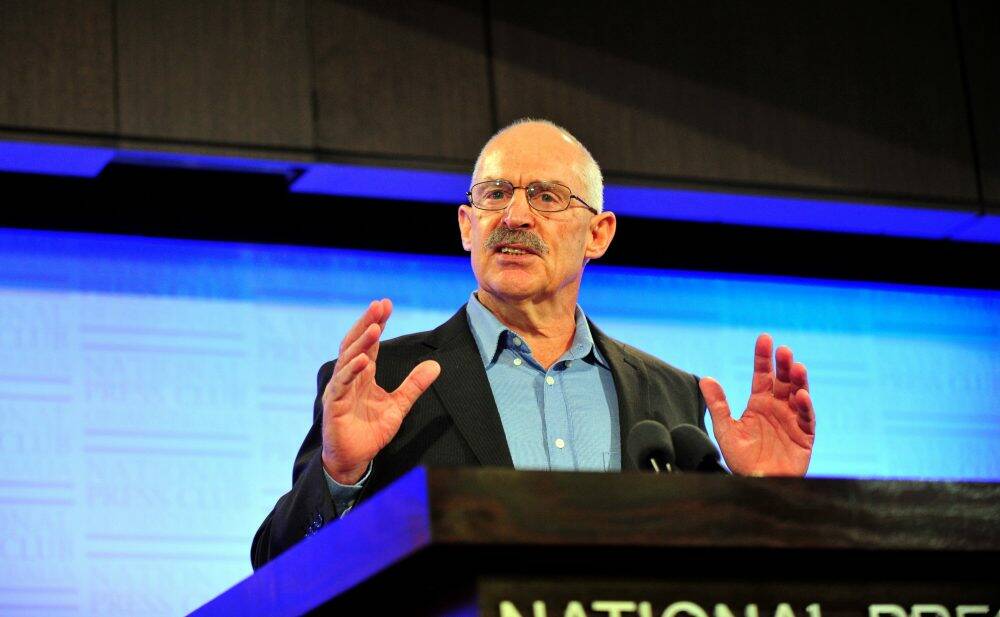

The story was just one Dr Kirby told in a speech to the National Press Club on Wednesday.

Timed to coincide with the lead-up to Mother's Day, Dr Kirby shared his experiences and the work he does supported by Canberra-based charity Send Hope Not Flowers.

For every 100,000 births in PNG 500 mothers die. In Australia only seven or eight mothers die, Dr Kirby said.

In Milne Bay, where he works, the rate is higher with more than 700 mothers dying for every 100,000 births.

“If a mother dies in Australia everyone the next day knows about it and that’s unacceptable, but in Papua New Guinea it happens every day … many times they’re not even reported,” he said.

“We’ve lost a bit of contact of how risky giving birth can be.”

Dr Kirby and his charity the Hands of Rescue Foundation is behind several initiatives to address the links in the chain that caused preventable deaths during childbirth.

It began with offering baby supplies to expectant mothers to encourage them and their partners to seek antenatal care and give birth in a medical centre rather than at home in the village.

He has also coordinated the building of homes for expectant mothers to stay close to the medical centre and continues to encourage PNG families to embrace birth control.

Dr Kirby described PNG women as “nation builders”, but said with few in positions of power in the male-dominated culture the problem of maternal mortality persisted.

“The male attitude towards women in PNG of course needs to improve,” he said.

“We started with our first radio play… we want to get the message to men … to say ‘You’ve got to attend antenatal clinics with your wife, she doesn’t need to deliver in the village and if you do get stuck and that placenta is not out in 30 minutes that’s a danger sign'.”

In September, Send Hope Not Flowers will celebrate its two-year anniversary helping to tackle maternal mortality in developing countries.

So far the Canberra charity has raised money reaching into six figures by encouraging supporters to make a donation in lieu of the money they would spend on flowers for loved ones in hospital.