During a recent stint in China, Sasha Grishin couldn't help noticing the presence of Chinese art. That is, the proliferation of Chinese art not just in galleries, but malls and other public places. And not just small pieces, but millions of dollars' worth.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

"What I did admire was how the Chinese big businesses really were behind contemporary Chinese art," he says.

"There are about 16 artists living in Beijing at the moment whose unit sale cost per item is over $US1 million. We don't have one in Australia, by the way, and we have about six in New York … John Olsen is probably our best-priced artist and his are a couple of hundred thousand. We don't have anyone within a cooee."

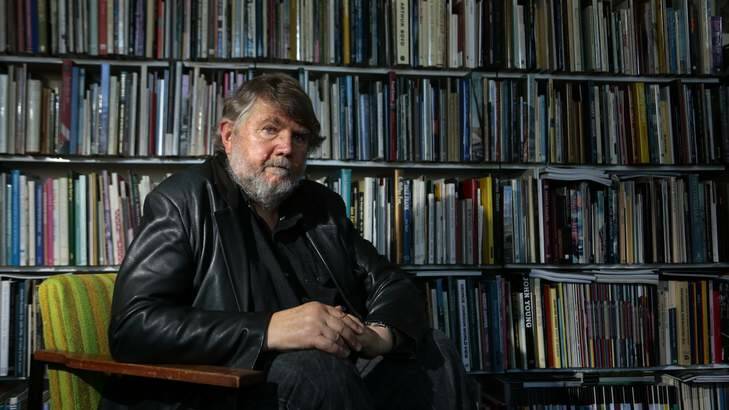

As a long-time scholar of art in Australia, it's something Grishin has long lamented - the difficulties faced by Australian artists to break into the market, to make a living, even to get noticed and assessed at face value.

"The bottom line is, I do think Australian art is fantastic," he says.

"I really believe that, and I think I've seen enough internationally to actually make that case. I think the best contemporary Australian art, the best 20th century Australian art, really stands up to any international competition, and I thoroughly believe in that."

It's this thinking, and this passion, that underpins Grishin's latest magnum opus - a lushly illustrated and beautifully produced 300,000-word history of Australian art, published this month by Melbourne University Publishing. It has, depending on how you look at it, taken 30 years to write, or really only the past six or seven - from the moment he realised that Australian art needed to be reassessed as a 200-year dialectic between indigenous and non-indigenous practice.

But the broad subject itself, and the subject of the book, has been a life's work.

"I've been working in Australian art professionally - writing, publishing - since the '70s. This is my 24th book and there are also a couple of thousand articles, most of which relate to Australian art. So in other words, I've been thinking of a lot of questions about how to tell a story," he says.

Not to mention the hundreds of reviews of art exhibitions he has filed for The Canberra Times over the years.

Why, then, did he decide to take on such a massive project? Grishin is adamant that nobody else has been brave or foolish enough to attempt it. Bernard Smith's Australian Painting: 1788-1960, published in 1962 and subsequently updated, only considers one medium, and only in the non-indigenous tradition. There have been other, more comprehensive works published since, by the likes of critic Christopher Allen and former director of the National Museum of Australia Andrew Sayers, but these, he says, have been notably short. "When you're doing something very, very short, you can get away with a sense of omission," he says.

"This book is about 300,000 words - there's a lot of verbiage. It attempts to look at the whole tradition of Australian art from the beginnings to the present, and it does go across most mediums … So it's an incredibly ambitious spread that I've attempted, and almost from the word go, you realise you're setting yourself up for failure. You can't do it."

But he has at least made a good go of it, even deciding early on to avoid compiling an anthology, and to instead focus on finding a narrative.

It came to him, he says, while on a research trip to London around eight years ago - his "eureka" moment. Fronting up to the Natural History Museum in London, he arranged to view all of the available material relating to the First Fleet - assuring staff he had put aside weeks to do so. "I just wanted to look at first contact art and to see what would happen then," he says. "And what I realised, which … I think to anyone else in retrospect is obvious, but wasn't to me at the time, when people came to Australia, they weren't only blown away by the unusual flora and fauna, the peoples and so on, they were also blown away by Aboriginal art. That I hadn't realised."

The first non-indigenous artists to depict Australia were, in other words, responding to the Aboriginal art they were seeing for the first time, in their own work.

"What dawned on me is that really, the history of Australian art is the history of a dialectic, between indigenous and non-indigenous art, and that the earliest contact art really has not aboriginal imagery so much, but aboriginal modes of visualisation, which is a whole philosophy," he says.

"Then a lot of things fell into place, and I realised when I was looking at indigenous art that the idea that this is some sort of tradition which is sealed and untouched by anything else is rubbish. All sorts of elements come into it. When we think about indigenous art today, we really are looking at an indigenous art that's been created with the knowledge of other traditions. It's certainly not isolated. ''This doesn't detract from it, and this is certainly not an argument for some sort of amalgamation, but it is impossible to look at one without looking at the other. And once I sort of saw this, then it became quite exciting - that really, all Australian art seemed to be this kind of ping-pong, 'this artist responding to things'."

It was, he says, the incentive he needed to embark on a new history, one he is certain will cause disagreements, if only because he suggests that Brett Whiteley was overrated, and Jessie Traill was the greatest etcher of the first half of the 20th century. It's less the assertions than the context that will shake feathers: Grishin takes pride in overturning long-held assumptions about the traditional hierarchy and structure of the artist galaxy. "I think one of the reasons why the lynch parties will be out is because the book, although it doesn't try to present a canon, does reassess things," he says.

"I suppose I'm a very naive person, but it struck me that I'm looking at things from the 21st century, and again, we've never been able to do that. We are really looking from a very different perspective, from a different age, with different tools and so on, and as somebody who's spent a lot of time in museums dragging out heaps of art, and several things emerged. One was that without being in any way ideologically committed, I realised I was writing-in a lot of women who had been excluded from the discourse."

Traill, the Melbourne-born printmaker who worked throughout the early 20th century and died in 1967, is one example - one he says renders the entire canon of Australian etching a one-horse race, easily eclipsing Norman Lindsay, Sydney Ure Smith and Hans Heysen. And yet she doesn't even rate a mention in Smith's history.

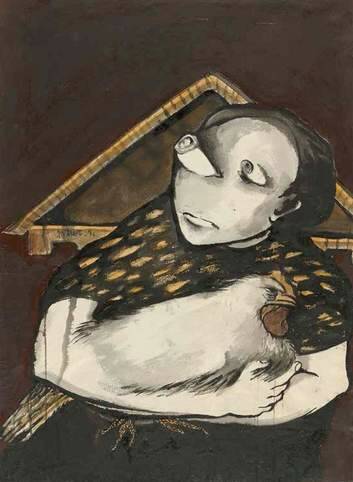

Another is Joy Hester, the modernist artist who was the only woman among the "Angry Penguins" of the Heide School, and briefly married to Albert Tucker.

"She was just so much better than Albert Tucker … he did some very strong images for a very short period of time, which obviously I discuss. But when I look at the great work of Joy Hester, she had everything going against her," Grishin says.

"She was a woman, she wasn't making paintings - she was only with Albert for a very short space of time - and the thing was that she was never taken seriously."

But Grishin says that by now he is immune to criticism when all he is doing is making observations. But for all his bold pronouncements, Grishin admits to a bout of cold feet as he got deeper into the work.

"I thought, you're starting to sound very much like a pompous arsehole - an opinionated pompous arsehole - perhaps you should get off your soapbox," he says. At his most educated guess - based on figures from recent Census data, the Australian Tax Office, the National Association for the Visual Arts, among others - there are between 25,000 and 35,000 professional artists working in Australia today, visual artists whose work is in a public collection and exhibited regularly in a recognised gallery.

"Even if I've got a rather generous allotment of words, I realised that my knowledge was going to be relatively limited, and I really didn't want the book, in the final chapters, to be a 'Sashbo's friends' type of thing," he says.

"This book will be a lingering smell for a very long time, because it's so expensive to produce and it comes with quite a bit of authority. So what I thought I'd do is ask artists who they thought were worthwhile." After much thought, he approached 80 established artists across the country - aged 30 to 90 and of roughly equal gender - and asked them each to nominate 50 living artists, working in any medium, who they believed were making a major contribution to the visual arts in Australia.

After assurances that all nominations and comments would be kept confidential, 68 of the 80 agreed - a figure Grishin describes as "bloody awesome". Even better: 63 of these later agreed to provide a separate list of 50 artists who they felt had been overrated. Armed with the two lists, he was able to present an assessment of the contemporary art world, from the perspective of the artists themselves.

"There was enormous overlap - not unanimous, but the overlap was substantial," he says. And were there surprises? Absolutely.

"For example, who was the most highly regarded visual artist in Australia? Bill Henson. That was the voice of the artists. And there were names of people who you didn't expect - for example someone such as [painter] Elisabeth Cummings had a very good innings."

(And for the record, David Bromley was an artist whom everyone approached agreed was "absolute crap".)

"That became the guide for my final and rather controversial chapters where I'm trying to weave my way," he says.

He is also keen to point out the book's carefully chosen title - Australian Art: A History - is one he fought for, being leery about any use of the definite article.

"Of course I don't want it to be one person's opinion," he says. "There's an enormous amount of scholarship that I have digested and in a fully academic sense of the word plagiarised and brought together, and certainly there's a lot of work done."

"I suppose in academe, there's a difference between publishing books because you feel you have to, and publishing books because you feel you've got something to say. This very much falls into the latter category," he says.

"I thought, I'm old enough to do it and I'm young enough to do it. In 10 years' time I may not have the energy to attempt something like this, because it basically meant most nights working on it."

Ultimately, then, the book has been a labour of love, and while he won't describe it as a masterpiece - he has at least two major projects on the go that rank equally highly among his works - he wants it to succeed in the way he has intended all along, as an advocacy for Australian artists. "I just believe that we really need to get our stuff out there, we should stop undermining ourselves," he says.

"My point of view as I get older … is if you go to a show and you see two or three really fantastic works, let's talk about those two or three fantastic works, not about the 47 others that are ordinary. Be positive about the good things, rather than just walk in and say, 'Oh lord, they've got three awful things, let's talk about them'. In Australian art, I think we've got such a galaxy of really fantastic artists, both indigenous and non-indigenous making art today, that it's really important for us to actually not lose sight of that, to not so much sing their praises but present an honest evaluation, because the stuff is good. Hopefully what I'm trying to do in this book is to show where a lot of this art comes from."

And most of the time, in the very best examples, Australian art bears a distinctive stamp - one that tells the viewer it could not have come from anywhere else.

"There's good contemporary stuff and there's bad contemporary stuff. I think the good contemporary stuff is never shy of where it comes from," he says.

"The bad contemporary art, why it's bad is because it looks like something else … [when it] really is derivative. It doesn't make it bad, but it doesn't make it very interesting, and I think the really interesting Australian art is things where you say 'right, I've never seen anything like this before'."

Here, he cites John Olsen, Bill Henson, Tracey Moffatt and Fiona Hall.

"It doesn't matter where they come from, they've become part of this place, partly because they've become involved with this dialectic with indigenous art, partly because with they've become involved with the landscape, the colour and the light and everything else. It's all reflected within. It's as vague and nebulous as that."

Australian Art: A History. By Sasha Grishin. University of Melbourne Publishing. $175.