The Canberra visual arts scene is always a crowded one, but 2013, even by Canberra standards, was an exceptional busy year. The main reason was the program Robyn Archer devised as artistic director for the centenary of Canberra celebrations. Every second exhibition held in Canberra was in one way or another linked with these celebrations and frequently received some sponsorship. This has certainly been the most successful program of visual arts events in Canberra's history.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

When asked to nominate the five most significant visual arts events over the past 12 months, at least one of these spots has to go to the Canberra Centenary program and to its mascot, Patricia Piccinini's Skywhale. It may have stirred the possum in the arts community, but what is of far greater importance is that it provoked debate among Canberrans who rarely set foot in an art gallery and for whom art matters are generally not on their radar.

Everyone had an opinion about this multi-nippled huge floating airborne whale which had a slight touch of the uncanny about it. If the animal is indeed nursing, one wants to ask: where are its young? I sincerely hope one day to look up into the Canberra night sky and see it filled with dozens of little skywhales.

Canberra has always been a little shy of the local product when it comes to art, but on the national art scene the Skywhale has been a huge hit, with guest appearance throughout the country. The Archer-Piccinini team have done Canberra proud and we should acknowledge their achievement as being one of national standing.

One of the most important and beautiful exhibitions of 2013 was Stars in the River: The Prints of Jessie Traill, held at the National Gallery of Australia. I have always felt that Jessie Traill was the finest etcher in Australia in the first half of the 20th century, and this exhibition proves it. While Norman and Lionel Lindsay have received star billing for boldness, Traill easily wins for subtlety and imagination and for the sheer power of the visual. As an etcher, she was the odd woman out and miles ahead of her male contemporaries. She was not a dainty little artist with a flare for the decorative, but a brilliantly inventive creator, who celebrated modern industrial marvels such as the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and power stations, as well as the mystique and romance of the bush. It was a wonderful exhibition which for the first time put a great Australian artist on the map in the public imagination.

Another great exhibition was held at the Gallery of Australian Design devoted to the maverick Australian designer Fred Ward. He moved to Canberra in 1952 to supervise the furnishing of University House and two years later he was appointed as the university designer, a post which he retained until 1961. He also designed furniture for the Academy of Sciences, the Commonwealth Club and later the Reserve Bank in Sydney, the National Library, Admiralty House and many other buildings. It is difficult to exaggerate the importance to the appearance of Canberra of Ward's designs; yet even before his death in 1990, he was being forgotten. The exhibition, plus a monograph devoted to the artist by Derek Wrigley, have done much to document his activities and to preserve a crucial part of Canberra's heritage. Ward's language as a designer was simple, unadorned and authentically Australian, something that few furniture designers in Australia presently manage to achieve. At least now we have a record of the work of one of our former greats.

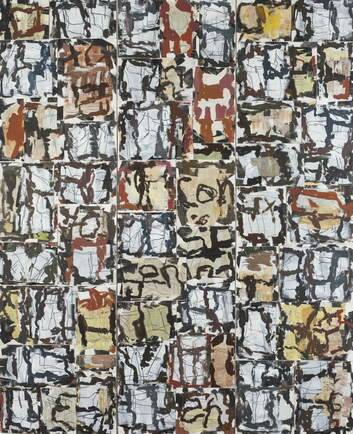

One of the most surprising exhibitions of 2013 was the brilliant Roy Jackson retrospective held at the Drill Hall and curated by its new director, Terence Maloon. While I have been aware of his art, but from that cluster of artists working out of Wedderburn, near Campbelltown outside of Sydney, who included the late John Peart, Elisabeth Cummings, David Fairbairn, Joan Brassil and Su Archer, he was the least-known. This exhibition showed him to be a brilliant creative talent, one who possessed a genius for conveying a sense of place or a sense of a sensation. It could be the effect of rain or the feeling of wind through the trees - or the experience of a memory of a poem, a passage of music, the act of love-making, or a specific event, such as an encounter with a dingo. There is a startled innocence about each individual work, as if it has arrived as a surprise, without fanfare. I am reminded of the wonderful aphorism by Jean Dubuffet, who once said that ''art … loves to be incognito. Its best moments are when it forgets what it is called''. It is this informal surprise which characterises some of Jackson's finest works. This exhibition makes a claim, for the first time, for Roy Jackson as one of the significant artists of our time.

The final exhibition that I would nominate in this very short list is Paris to Monaro: Pleasures from the Studio of Hilda Rix Nicholas, which was held at the National Portrait Gallery. The commonly held view that the artist got progressively worse as a painter after her return from Europe, where she was flirting with modernism and Orientalism, and that she deteriorated after she settled on the land, is challenged by Sarah Engledow's exhibition. While it is true that as she settled in Delegate she valiantly tried to graft the lessons from abroad to the Australian pastoral tradition and produced a heavy-handed nationalist painting, it was a distinctly female vision of specifically Australian pastoral life. In her paintings she had a wonderful expression of intimacy, as well as an empathy for caring for animals, children and the environment. It was also a mature person's artistic vision, distilled and resolved, and in contrast to the vivid and spontaneous sense impressions of some of her earlier work. The exhibition gives us a new perspective on a little-known episode in the life of an important Australian artist.

Outside of Canberra, one of the exhibitions which is attracting a huge following is Melbourne Now at the National Gallery of Victoria, which examines Victoria's visual culture of today. On my wish list for the future is a national exhibition in Canberra that could be called Australian Art Now. It is overdue and only Canberra could stage it, if several of its national cultural institutions joined forces.