In 2014, after Edward Snowden leaked documents which revealed just how capable the US National Security Agency was at keeping tabs on global electronic communication, a German politician in charge of a committee investigating those allegations made a radical suggestion for avoiding surveillance.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

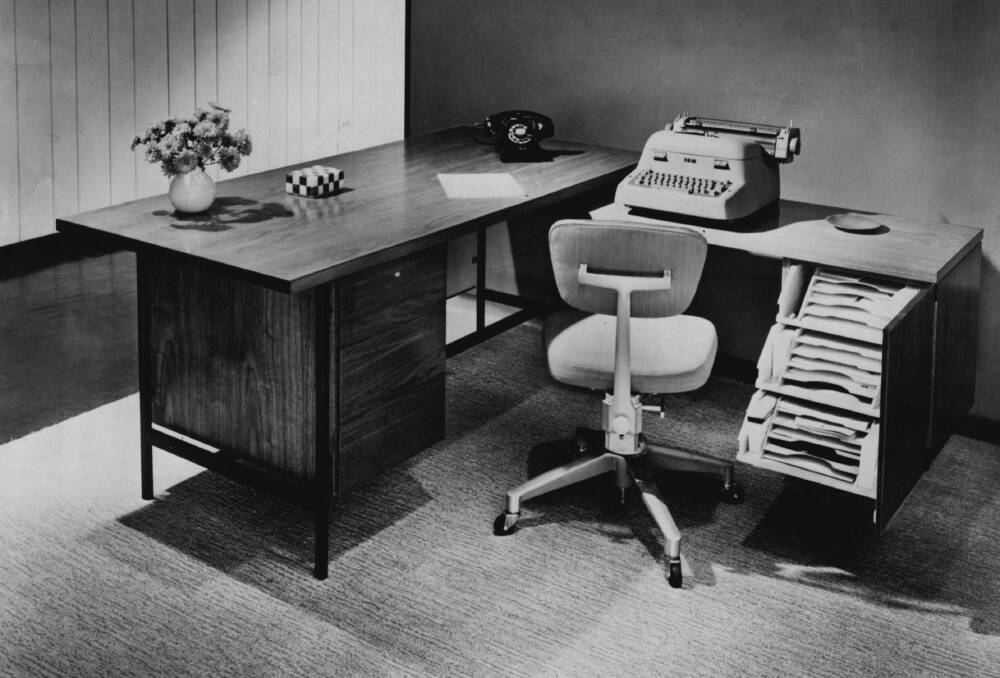

Patrick Sensburg told an interviewer on the Morgenmagazin program the committee was considering typewriters - and not the electronic kind.

It seemed like a perfectly sensible suggestion to me. I got my first typewriter at the tender age of seven. A Smith-Corona Galaxie Deluxe bought for me by my father for $10. He takes some of the blame for what followed.

It has been said Canberra - a city of academics, public servants, university students, journalists - was a good breeding ground for typewriters: a city where anyone who was anyone needed at least a portable. This made it almost too easy for me to amass them as a teenager, in a golden era when they were superseded technology but had not reached the heights of hipster status.

The number in my collection is now somewhere between 80 and 90. Asking me to pin down an exact figure is a cruel question. They're all different, I promise, even if only subtly. And what's the attraction? They exist, they're real, they don't break down in a hurry, you can blast them with a garden hose and still produce lines of text. They are real things in a world of imagination, simulation and mirage.

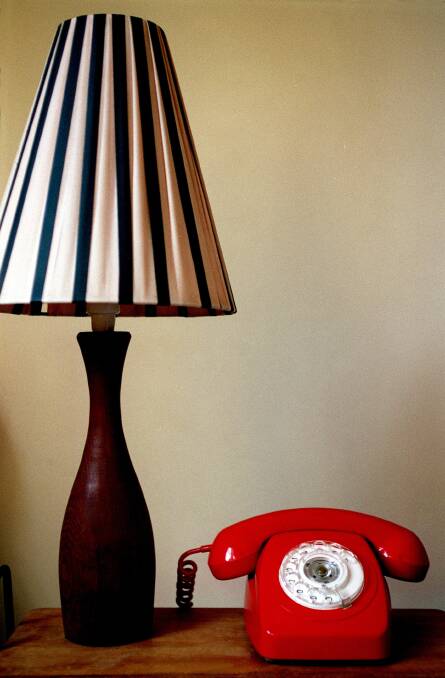

I have always had a penchant for anything outmoded. I'm the only person I know under 25 with a home phone number, which, if you ring it, I'll answer on an Australian-made standard issue Telecom Australia 802 model phone: the one with the curly cord, rotary dial and real-life bell.

Naturally, there's a turntable at home, too - but that hardly counts anymore. Everyone knows vinyl is back. The AM radio has perhaps less street cred. I've started listening to Radio National of my own choice about 25 years ahead of the normally mandated age.

I was encouraged at school to write with a fountain pen. That's stuck too, an elegant anachronism - some might say affectation - of carrying around ink prevented from leaking everywhere by little more than some metal with a slit. I'll tell anyone who'll listen the best writing paper is made in France and the best pens in Germany. I'd rather work on paper than on a screen.

And attached to my desk in the Canberra Times newsroom, much to the amusement of colleagues, is a rotary pencil sharpener. When you want to make a point, it pays to have a fine one on your pencil.

As you might have guessed, I'm a little bit perturbed by technology and the internet. Although, for all the ills it has caused, the net did cure boredom. Stare meekly at the road no more when you have to wait for a bus. Avoiding the tired, dated, well-thumbed copies of National Geographic in waiting rooms has never been easier.

But what if those moments of mental tedium were important, what if delayed communication was better for us and what if we are now on the path to digital damnation?

What if moments of mental tedium were important? What if delayed communication was better for us and what if we are now on the path to digital damnation?

Nicholas Carr asked more than a decade ago whether Google was making us stupid in a long essay for The Atlantic. Carr felt his mind changing and that he no longer thought the way he used to. He concluded that "as we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens into artificial intelligence".

Richard Polt, a philosophy professor at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, is currently testing that theory to the extreme, stepping away from unnecessary digital devices during his summer break.

Professor Polt, an expert on Martin Heidegger and the author of The Typewriter Revolution, published in 2015, announced on his blog in May he would have some digital rest, away from computers, email, smart phones and eBay.

He hypothesised he would feel "boredom, isolation, unsatisfied curiosity, inconvenience [and] irritation" but also "peace, concentration, balance, creativity".

"Maybe this will be like time travel to the first half of my life, when I inhabited an 'analog' world - or should I just say the real world?" Professor Polt wrote.

This plan made me wonder how I would think away from the digital information slipstream? I've never had the chance as an adult. Would my concentration improve? Would I finally pluck up the courage to delete my Twitter account? Would I call it time on Facebook, which too often seems like a necessary evil?

It's not that digital technology is inherently bad. Mapping the human genome has been excellent and don't get me started on my love for Trove, the National Library's digitisation project that lets anyone with the internet pore over historical maps, newspapers, letters, gazettes and pictures.

The speed is what makes me wary. A typewriter reminds you that there's elegance to being slowed down, allowing yourself time to think, pushing against the sheer weight of it. A dial phone reminds you to get the phone number right the first time - and to remember it.

I've come to see my affection for pre-digital means of living as part of a broader attempt to test what effect computer technology has on us who never really knew a world without it.

There's no simple solution to the madness of constantly interconnected, digital living. There's no easy way to reclaim those precious moments of boredom.

But one day, I like to think, I might come across an answer in a card-index file - probably alongside the records of that German committee's proceedings.