Secrets of a sordid past are returning again to haunt the Marist Brothers in Canberra, with a new publication this week revealing a priest alleged to have sexually assaulted one young man more than 100 times served in a teaching role in the ACT in the early 1980s.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

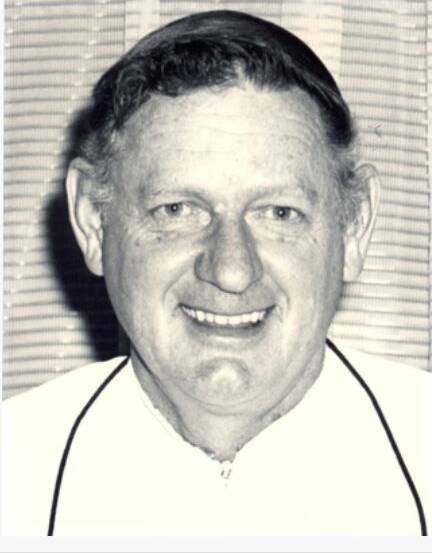

Brother Geoffrey "Coman" Sykes, now deceased, taught year 10 in Canberra in 1982-83 and coached rugby for the school.

Marist College Canberra was seen as the worst Catholic school in the nation when it came to child sex abuse, with 63 claims of sexual abuse made during the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse.

Former student and now Bravehearts ambassador Damian De Marco believed the total number of victims at Marist College Canberra would be much higher.

Notorious paedophile priest John "Brother Kostka" Chute also taught at Marist College in Canberra during the 1980s. Chute had pleaded guilty in 2008 to a large number of historical sex abuse charges against 19 children and spent at least two years in jail.

He subsequently faced 16 charges against six victims between 1979 and 1986, including 14 counts of indecent assault of a minor, one charge of buggery without consent and one charge of an act of indecency with a minor. He was found unfit to plea last year.

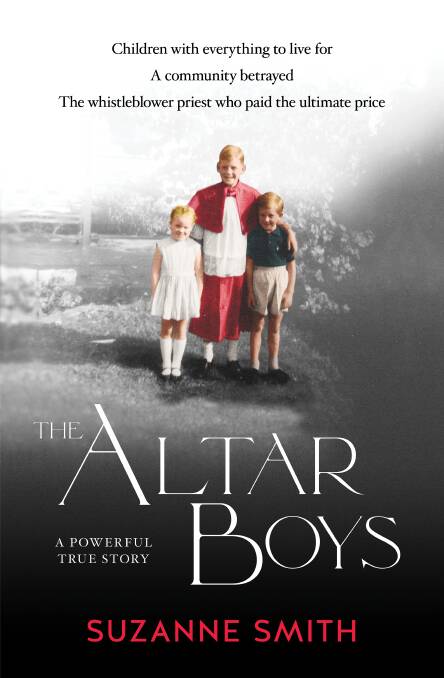

The latest revelations about Sykes, published in the book Altar Boys, follow on from previous allegations against Marist staff in Canberra, including those against a former headmaster, Brother Christopher Wade.

Brother Wade, also known as William Henry Wade, was the headmaster of Marist College Canberra from 1993 to 2000, when he retired. The indecent assault charges stem from his time at Marist College Kogarah in the late 1970s, well before he arrived in Canberra. He was jailed by a Sydney court for a minimum of nine months in November 2017.

Brother Sykes, described by author Suzanne Smith as an influential and senior team leader, was one of two Marist Brothers who devised a plan in the early 1970s for a series of "retreats" for young men who may aspire to the priesthood.

One of the retreat locations was at a stately home in Mittagong, in the Southern Highlands.

Ms Smith described how Sykes and another brother came up with an effective selection process for the retreats, one that involved identifying the "better boys".

It was Sykes' belief that if they could get a "group of their better boys to Mittagong for a leadership course ... for a few days during school time, then after some good liturgies and a faith experience, they might be ready to talk about vocations to the priesthood or a religious life", the book says.

Brother Coman had been involved in a growing movement, the Christian Living Camps, since the 1960s. The formation of the Youth Retreat Teams within the Marist Brothers was his brainchild.

Students at Marist Brothers schools in Sydney, Maitland, Newcastle and Canberra participated in the program.

It was during these retreats that Brother Coman Sykes was to prey upon a powerless student, Glen Walsh, and commit acts of numerous acts of indecency on him.

Raised in Newcastle, Mr Walsh aspired to becoming a brother and trained as a live-in "postulant" at the Catholic Teachers College in Sydney's Castle Hill.

Brother Coman, then 52, lived on the lower floor with the new recruits and was responsible for the postulants' "spiritual formation". He showed a particular interest in Glen and when the young man fell ill, suggested he recuperate at a house at Leura, west of Sydney.

It was at that Marist brothers-owned house where Brother Coman, 34 years older than his victim, preyed upon the young man, sexually assaulting him on an almost nightly basis.

In the end, after around 100 such assaults, Glen Walsh left the order in May 1981.

As Ms Smith described in her book: "He'd had enough of being a target."

A little over a year later, Sykes was in charge of year 10 boys at Marist College in Canberra.

Mr Walsh remained a devout Catholic and after a lengthy break which included teaching on a remote island off Papua New Guinea, he returned to join a seminary, studied to become a priest and was later ordained.

Tragically, he later committed suicide when the Church and the Bishop, to whom he confided Sykes' offences against him, failed to acknowledge its misdeeds.

In 1995, the wall of silence which had protected the Catholic priesthood started to tumble with the charging of Father Vince Ryan, whose range of sexual abuse offences against dozens of young men over a lengthy period of time became national news.

"The Church hierarchy, until then, had thought the police knew their place when it came to Church business," Ms Smith wrote in Altar Boys.

"There was an unsaid pact that officers wouldn't pry too much into Church affairs. When similar complaints had been made to police, these matters had been handled in secret; the Church had moved the offending priest out of the jurisdiction.

"But now stories of clerical paedophile clusters were hitting the media, and ... the veil of secrecy was slowly being lifted."

Father Ryan's car was seized and examined. In it they found a list of altar boys, all victims, with a cross drawn next to each of the names.