Ian McFarlane

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

My favourite books for 2022 are all non-fiction, starting with Philip Deery's look behind the masks of Australia's domestic spooks during the Cold War with his Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War. A "sparrow" was ASIO's code name for ordinary people recruited to penetrate Communist Party branch meetings in the politically tangled aftermath of World War II.

Similar passions, this time with a literary background, carried Nathan Hobby's beautifully crafted biography, The Red Witch: A Biography of Katharine Susannah Prichard. Prichard's fierce intelligence and independent thirst for social justice saw answers in communism following the Russian Revolution, as did other writers and intellectuals at the time.

Profoundly saddened by ideological arguments and selfish opportunism delaying climate change action, I was pleased by two excellent books on sustainability and science: Tim Hollo's Living Democracy and Humanity's Moment by Joëlle Gergis. Hollo explores achievable survival innovations, while Gergis patiently explains how science demands urgent remedial action.

Frank O'Shea

My two most memorable books were set in Australia, one in the 1960s and the other in our present day. Mark Lambrell's The Secret Wife is a story of friendships, set in what we didn't realise was the innocent decade when the world was opening up to new experiences.

I felt that I recognised the characters in Lambrell's story, which is more than I could say about those in Richard McHugh's The Cutting. The central character is a FIFO worker in Western Australia. His world falls apart when his boss has the ground literally taken from under him by clever Korean investors. The attraction is partly the story but also the sharply clever writing. I described the book as "a brilliant treatment of modern Australia".

Michael McKernan

Three outstanding books this year gave me my greatest reading pleasure in 2022. Gideon Haig surprised me, moved and overwhelmed me with his account of the early life of H.V. ("Doc") Evatt (The Brilliant Boy: Doc Evatt and the Great Australian Experiment). Haig showed readers what a remarkable and talented Australian Evatt was with ongoing importance in our national life.

Discerning readers of Australian history have come to hold Professor Henry Reynolds in the highest regard. With Nicholas Clements he gave readers an insightful, thrilling and deeply moving account of the life of a Tasmanian warrior/leader and guerrilla fighter, trying desperately to save his country for his people in Tongerlongeter: First Nations Leader & Tasmanian War Hero.

Writing the review of Mike Carlton's account of the Royal Australian Navy in the Mediterranean gave me the greatest writing pleasure I enjoyed this year. I wanted to acknowledge Carlton's love affair with the navy across several books now (The Scrap Iron Flotilla Australians at War in the Mediterranean). Carlton's knowledge, his skill as a writer, his passion and his respect for the past was on full display in this very readable contribution to Australian military history.

Karen Viggers

2022 has been a rich year for fiction, but here are three favourites. Willowman by Inga Simpson is a highly accessible cricket novel that is also a literary delight. Alan Reader, a bat maker, attempts to craft the perfect bat for a young cricketer, Todd Harrow, who is making an impression in the Sheffield Shield. Who would have thought bat making was such an art? An excellent companion to the summer cricket season, even if you're not a cricket-lover.

A Brief Affair by Alex Miller is another wonderful read. Nobody writes love, marriage and the inner life like Miller. Partly set in a lunatic asylum now converted to a modern workplace, this book calls into question who is more sane - past inhabitants of the asylum or those pushing a modern world.

Limberlost by Robbie Arnott is a beautifully crafted novel set on a river in northern Tasmania. It charts a summer during which Ned, a young man whose brothers have gone to war, hunts rabbits to earn money for a boat. Arnott combines the natural world with the personal to create an intimate reflection on life. Earning a boat and then renovating it is Ned's way of building memories back to his brothers.

Nigel Featherstone

Jessica Au's Cold Enough for Snow is a masterclass in allowing the tiniest of gestures to live wondrously, while The Grass Hotel by Craig Sherborne is an inventively devastating exploration of dementia.

Inga Simpson's Willowman, Pirooz Jafari's Forty Nights, George Haddad's Losing Face, and Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens by Shankari Chandran all provide fresh insights into what makes this thing called Australia.

A Burruberongal woman of the Darug Aboriginal Nation, Julie Janson's Benevolence is a heartbreaking novel that reveals the insidious foundations of colonial Sydney.

Works of international fiction that continue to resonate are The Perfect Golden Circle by Benjamin Myers (male friendship and crop circles), At Certain Points We Touch by Lauren John Joseph (one of the most beguiling love stories I've ever read), and Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (Ireland smothered by the cloak of religion).

The Burnished Sun by Mirandi Riwoe is an exquisite collection of stories about the repercussions of racism. Two nonfiction works that I continue to think about are Fugitive, in which concert pianist Simon Tedeschi offers a memoir in fragments, and Faith, Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Sean O'Hagan.

The poetry collection that undid me entirely was Ocean Vuong's Time is a Mother - it is both inventive and accessible, and very powerful indeed.

Robyn Ferrell

My favourite book this year was The Shortest History of Democracy by John Keane. Although it sounds dry, it actually really stimulated me to think about what we all take for granted in Oz- the blessed banality of the sausage sizzle on polling day.

Penelope Cottier

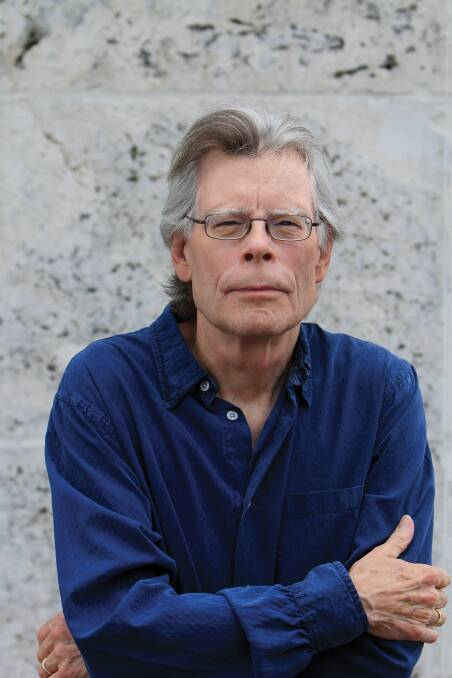

Steffi Linton's 28-page debut collection of poetry More to Lose packs quite a punch, covering topics such as hunger and body image in visceral and well-crafted poetry. Fairy Tale, Stephen King's latest novel, puts the horror back into an often bowdlerised form of literature. An engrossing and vivid work, showing King at his finest. Finally, Willowman by Inga Simpson crafts a complex and moving tale out of cricket. From those who reach the highest level of the game, to those who make bespoke bats, to the emergence of the women's game, the novel covers a wide field.

Jasper Lindell

The best new novel I read this year was Sophie Cunningham's This Devastating Fever, a brilliantly weird book that explores the history of Leonard Woolf's life in parallel with the early parts of the COVID-19 era in Australia. Woolf, the husband of writer Virginia Woolf, becomes a distinct and intriguing figure in Cunningham's deft novel.

Sally Olds' People Who Lunch: Essays on work, leisure & loose living was a sucker-punch of clever thinking, a slender volume of big ideas and form-stretching writing. Olds' essays do that rare thing of being enjoyable to read and still have thoughts worth being provoked. The Beautiful Piece, about the nature of contemporary essay writing, is worth the price of admission alone.

And I can tell, a chunk of pages in to this formidable tome, Norwegian author Jon Fosse's novel Septology, published in a single-volume edition with a translation by Damion Searls this year, will absorb me completely over the summer. It's the ruminating story of an old painter going over his life, rewarding slow and careful reading.

Alison Booth

Frank Bongiorno's latest book, Dreamers and Schemers; A Political History of Australia, is bound to become an Australian classic. An absorbing and scholarly account of Australia's political history, it is also beautifully and accessibly written, and leavened by occasional flashes of humour.

I also loved The Colony by Audrey Magee, a clever, exquisitely written story of colonialism set on a remote island off the western coast of Ireland. The plot centres on the conflict between a visiting linguist and a visiting artist, each of whom is exploiting the few remaining island inhabitants.

My third choice is Nigel Featherstone's novel My Heart is a Little Wild Thing, a tale of a gay man experiencing a late and tender love affair, whilst also being conflicted about family duty and the need to be true to himself.

Colin Steele

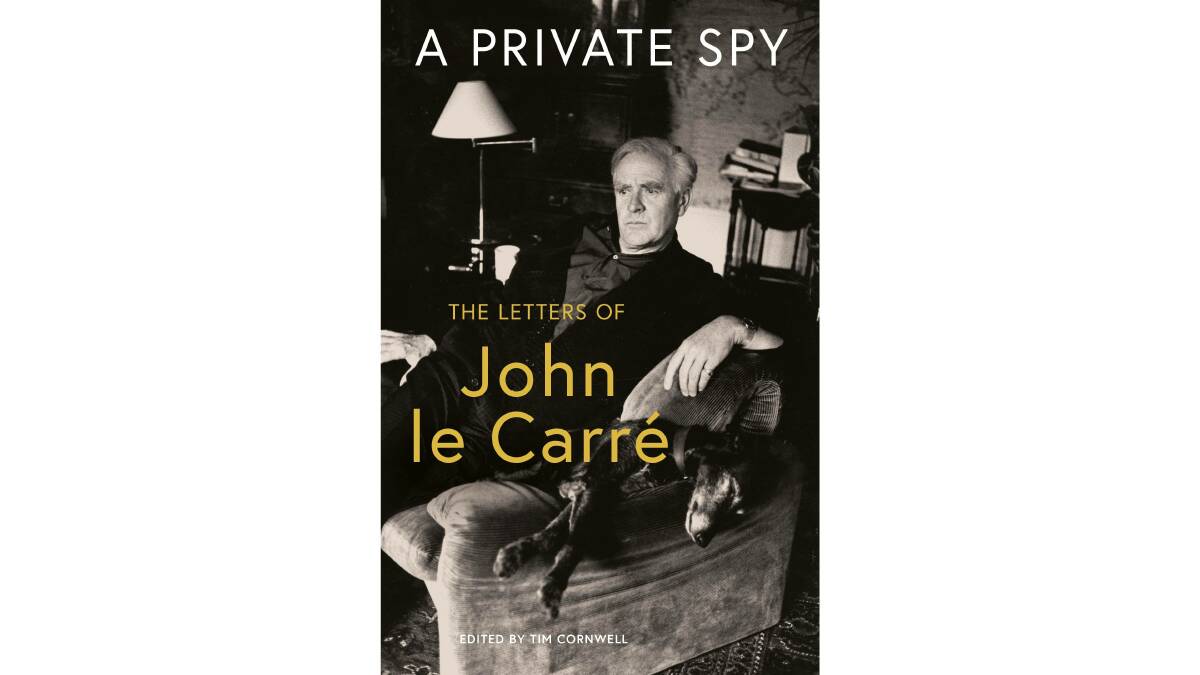

In nonfiction, A Private Sky: Letters of John le Carré 1945- 2020 illuminates a complex public and literary figure; Simon Sebag Montefiore's massive 1300-page The World confirms that we don't really learn from history, while The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen reaffirms the importance of libraries and the conservation of knowledge in an era of fake news and digital complexity.

In fantasy and SF, two Canberra authors stand out. Daniel O'Malley's Blitz cleverly juxtaposes the supernatural in 1940s London and the present day, while in 36 Streets former diplomat and aid worker T.R. Napper dramatically explores Chinese geopolitics in a future Vietnam.

Outstanding nonfiction books from the 47 ANU /Canberra Times meet the author events include Kylie Moore-Gilbert's harrowing, yet uplifting, The Uncaged Sky. My 804 days in an Iranian prison. Frank Bongiorno's Dreamers and Schemers provides a refreshing new perspective on Australian history, while Brett Mason in Wizards of Oz reveals how Howard Florey and Mark Oliphant helped win World War II and shape the modern world.

Gordon Peake

Most entertaining of all was Candice Millard's River of the Gods, a historical adventure story about the rivalries of English adventurers as they searched for the source of the Nile. It's a wonderful after-dinner speech to a historical society sort of book.

My eldest son came up with the perfect description of Simon Winder's Lotharingia: "Horrible Histories for Grown Ups." It's a vivid, rollicking, tongue-in-cheek history of centuries of mad kings, demented queens, scheming knaves, and assorted hangers-on in large swathes of the area we now think of as Western Europe. Winder is incapable of writing an uninteresting sentence.

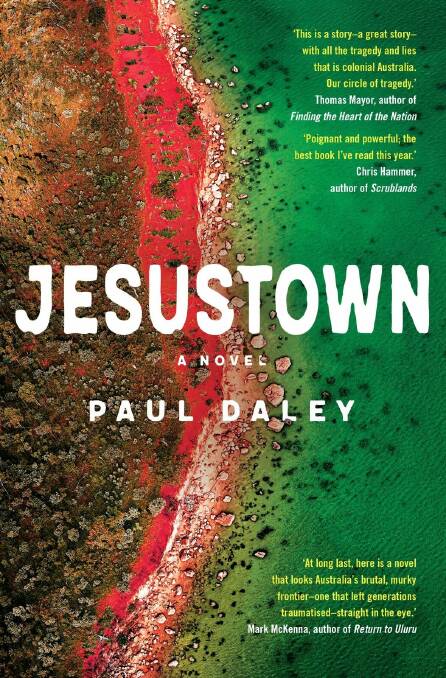

In terms of novels, Paul Daley's Jesustown, about family secrets and personal reckonings with Australia's dark past, deserves every plaudit it has received. I've been reading John Le Carre's "Smiley" series in order. There is no better chronicler of either the human condition or intrigues of bureaucratic politics.

Russell Wenholz

Jess Kidd's The Night Ship was my favourite 2022 book - fiction based on fact. Kidd tells the story of a young girl travelling to the Dutch East Indies on the Batavia in 1629. Her story is cleverly combined with that of a young boy living on the Abrolhos Islands in 1989. Their portrayals and their tending to supernatural connection in the context of the doomed ship and the barren islands retains realism.

Amy Walters

Maggie O'Farrell's ninth novel, The Marriage Portrait, makes clear what much of the commentary about her previous one, Hamnet, missed: that her interest is in women's lives. Inspired by the rumour that Lucrezia de'Medici was murdered by her husband Alfonso, the duke of Ferrara, O'Farrell paints a speculative picture of a young woman's doomed resistance to the tyranny she was born into. While not all of it is subtle, it excels in the understated way it talks back to Robert Browning's dramatic monologue My Last Duchess.

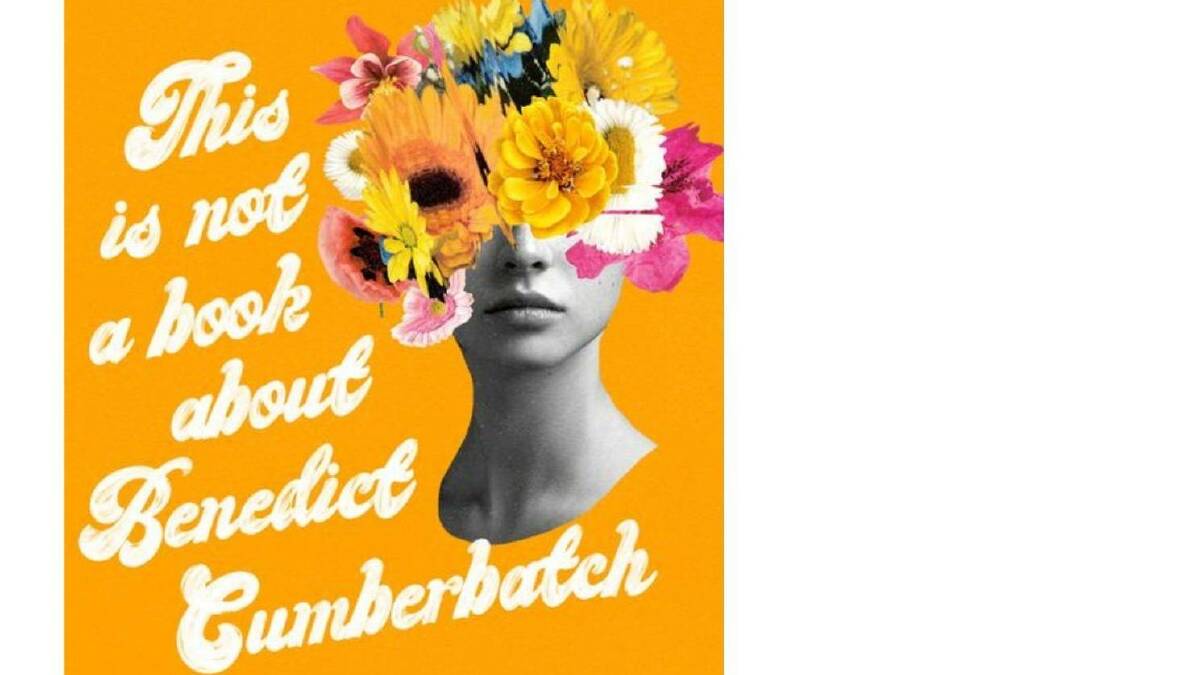

This is not a book about Benedict Cumberbatch by Tabitha Carvan, springing from Carvan's obsession with the eponymous actor, evolves into a moving examination of fan culture and asks why men's obsessions are treated more seriously than women's. It is a memoir that interrogates the underappreciated labour of motherhood but is also a masterclass in cultural criticism.

Mark Thomas

Rewriting history demands artfulness as well as art, craftiness in addition to craft. Any beer connoisseur is familiar with the inscription from the Sam Adams brewery in Boston ("Sam Adams, brewer and patriot"). Similarly, any admirer of love poetry - in its most intense, passionate, eloquent form - will know many of John Donne's poems by heart.

Nonetheless, The Revolutionary by Stacy Schiff and Super-Infinite by Katherine Rundell delve deeply and thoughtfully, dramatise and question, scrutinise and bring back to life Adams and Donne. Both emerge as more intriguing and more human than we have known them before. The two books are remarkably incisive, insightful and intelligent. In the same spirit of rediscovery and reinvention, Dan Fesperman's new thriller, Winter Work. has as its main characters senior agents in East Germany's dreaded secret police (the Stasi), caught when their creed and careers shatter. If not sympathetic, they are richly and cleverly imagined.